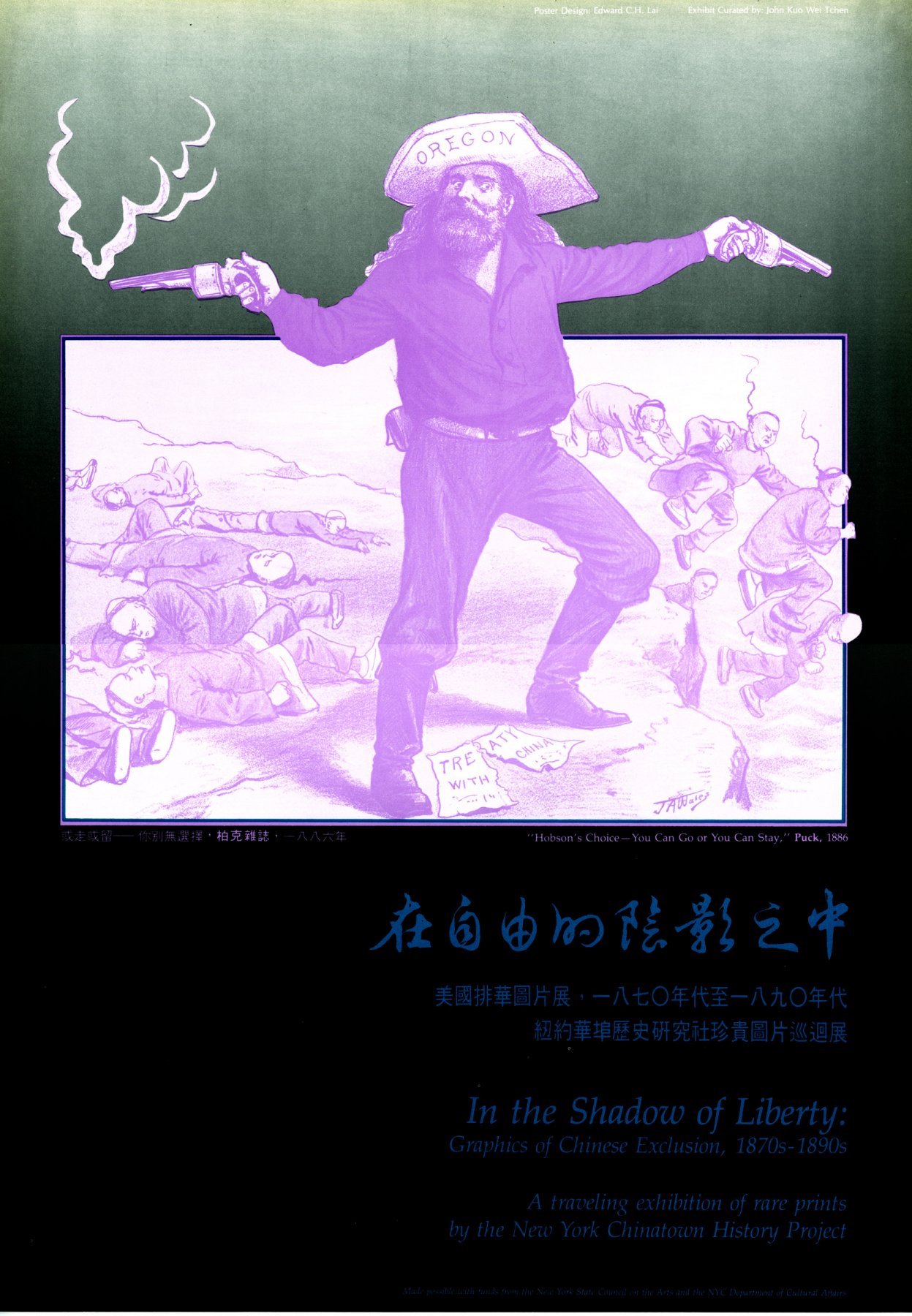

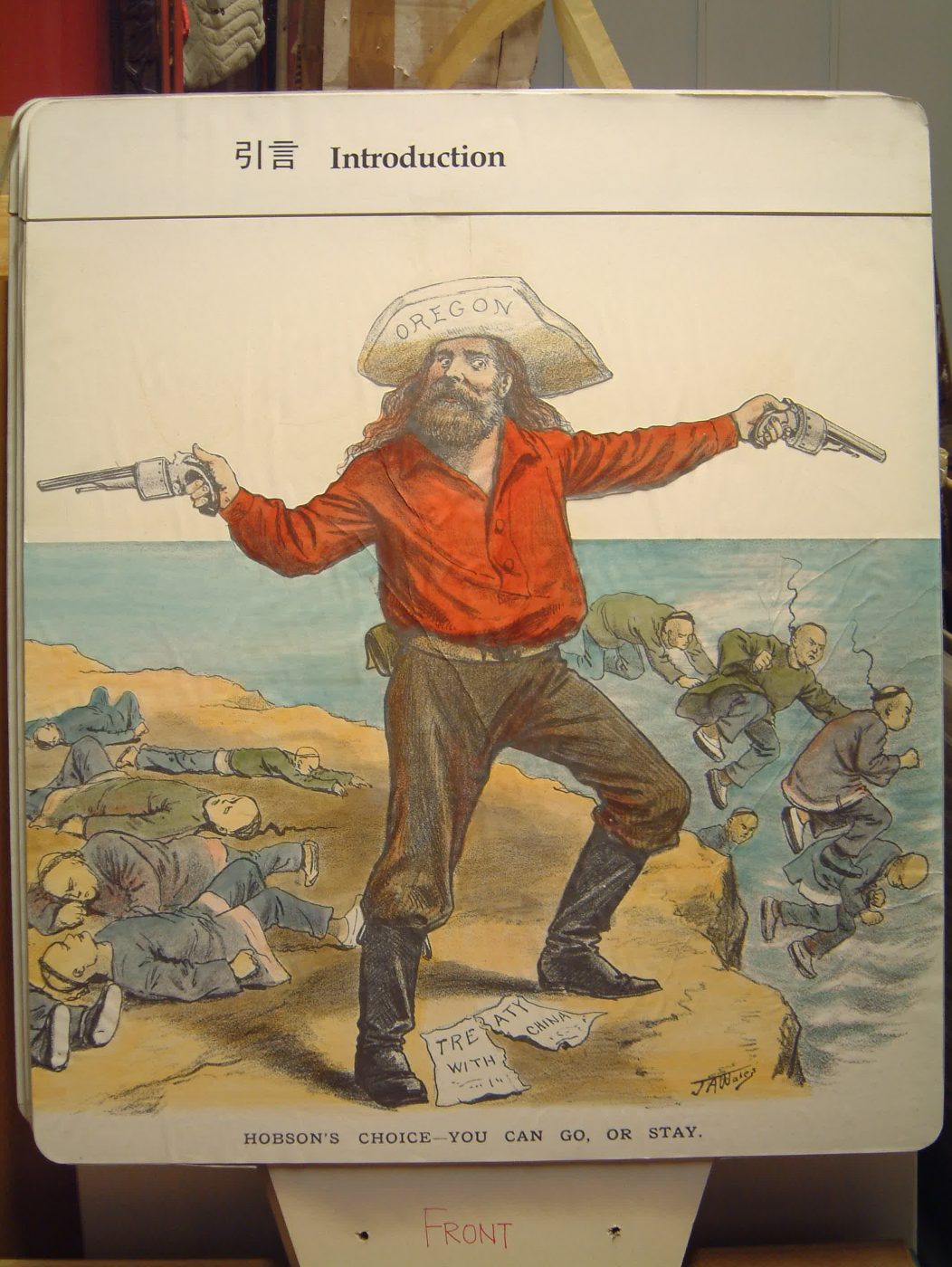

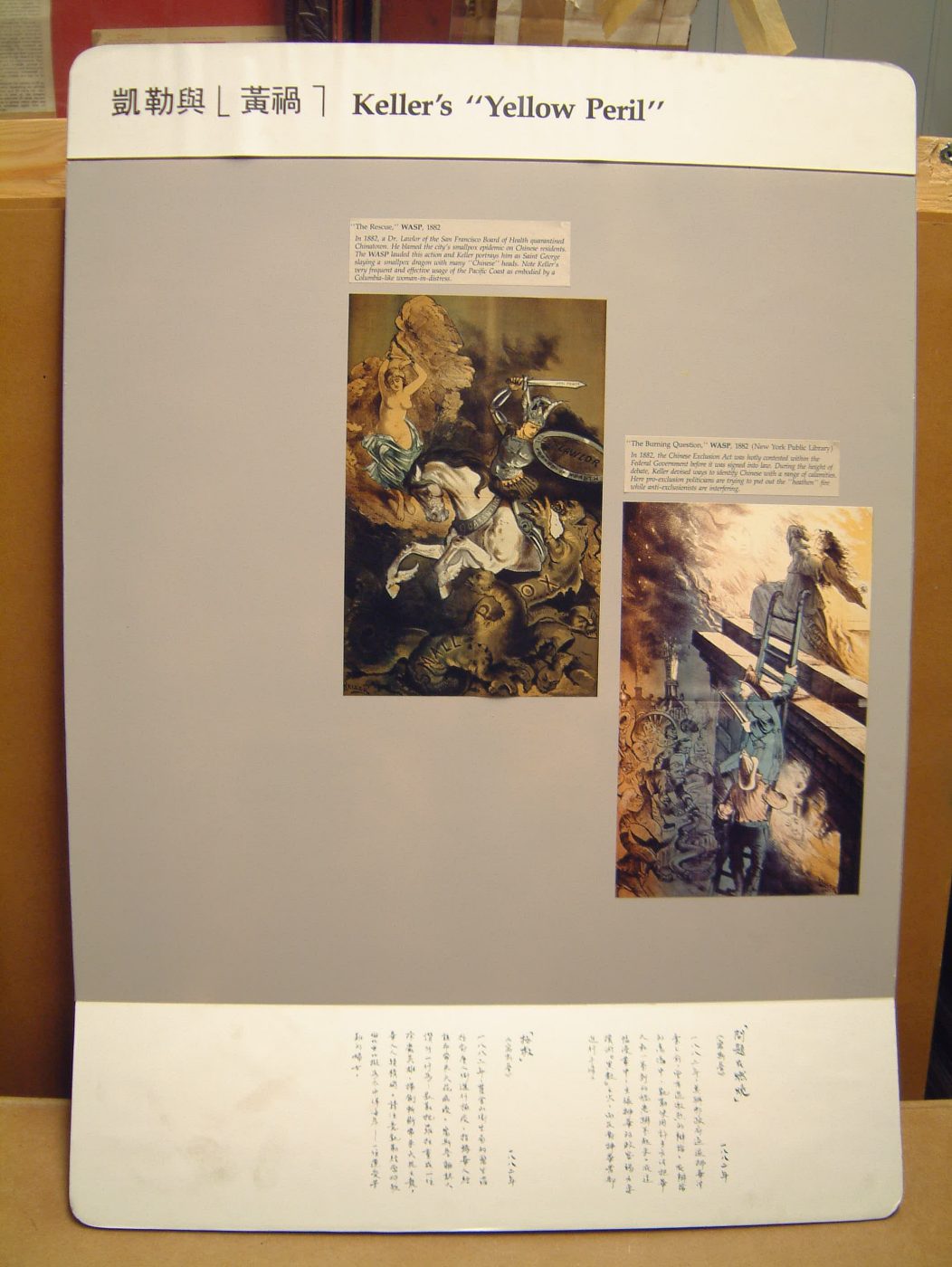

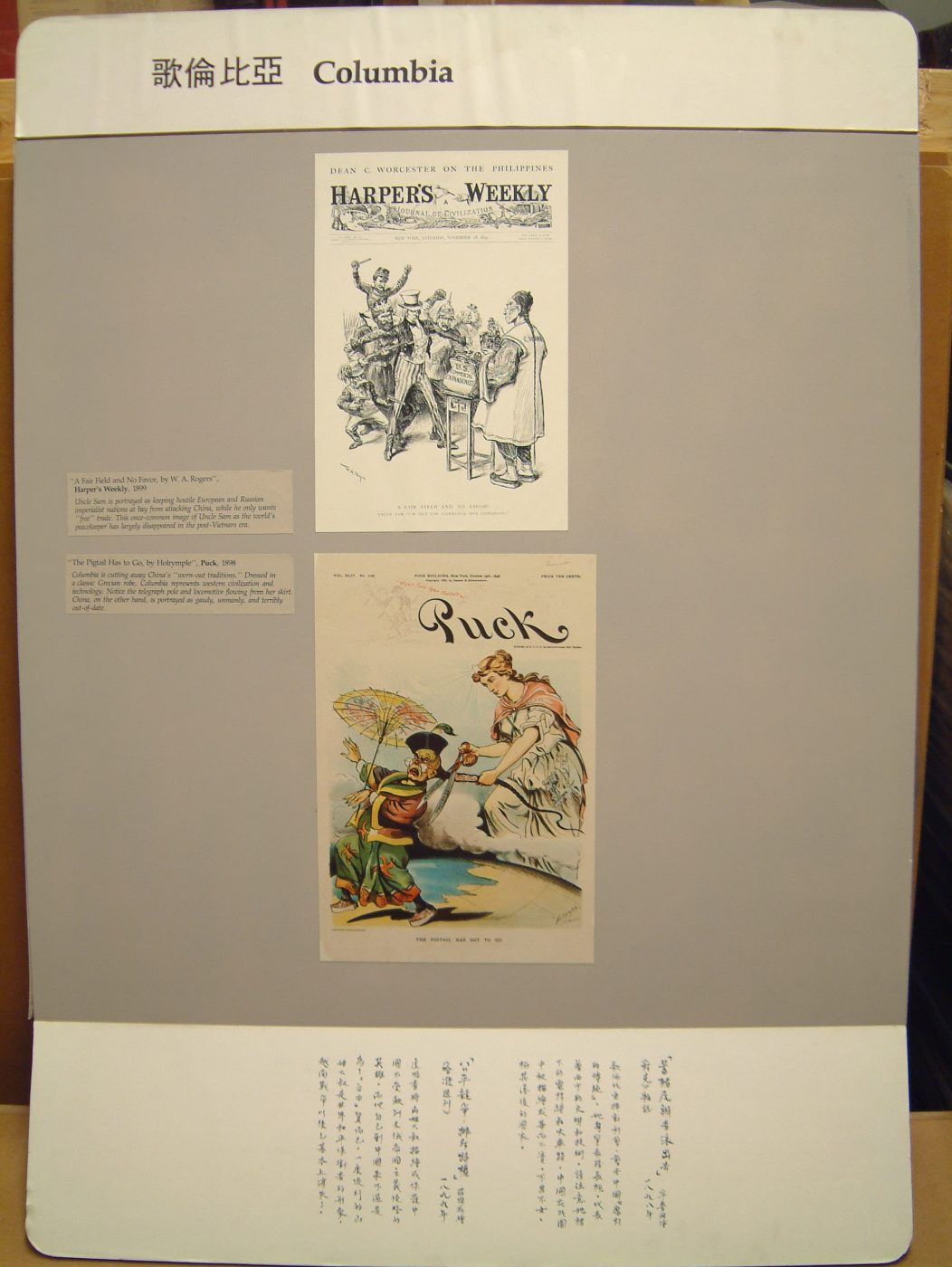

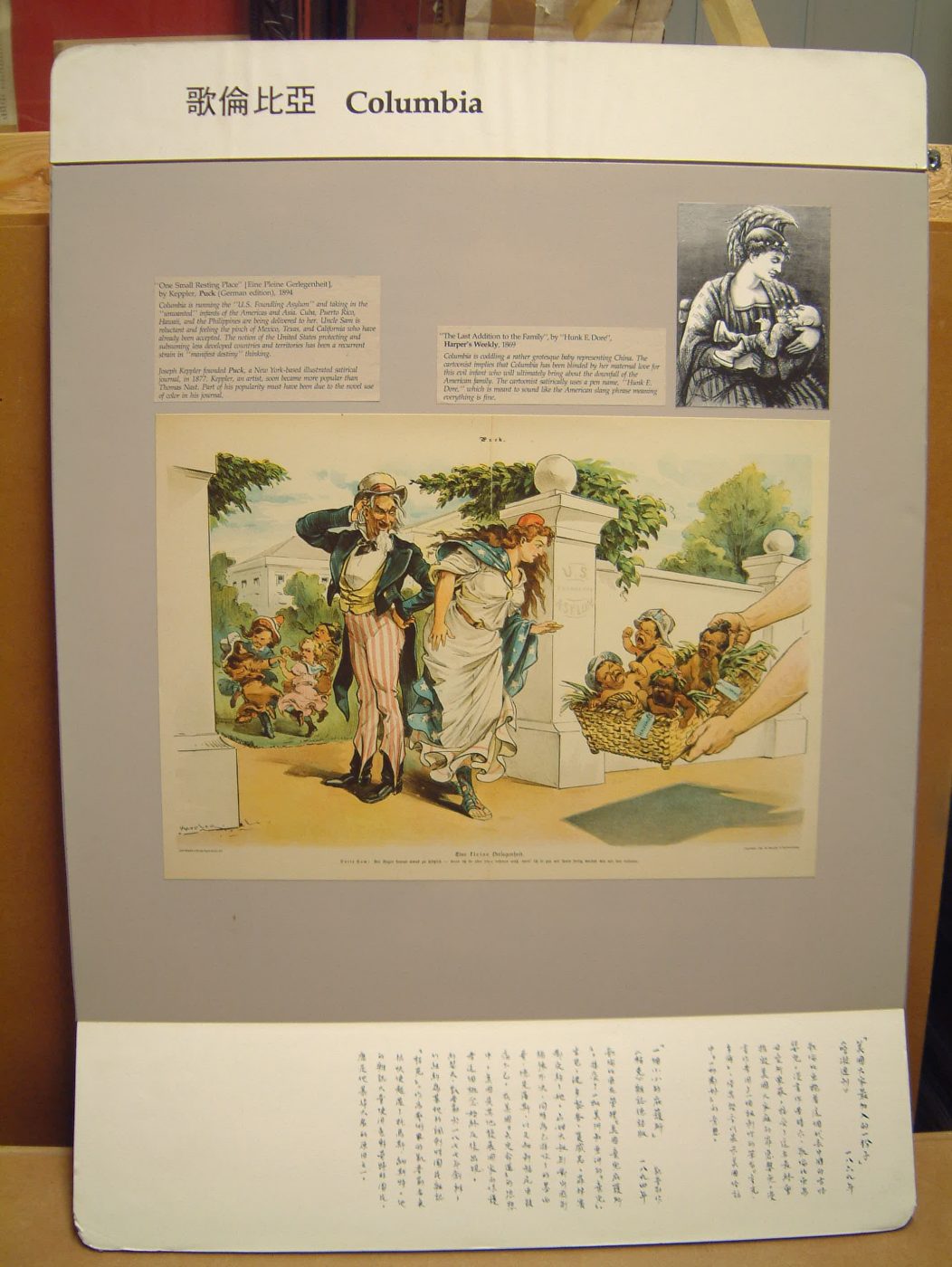

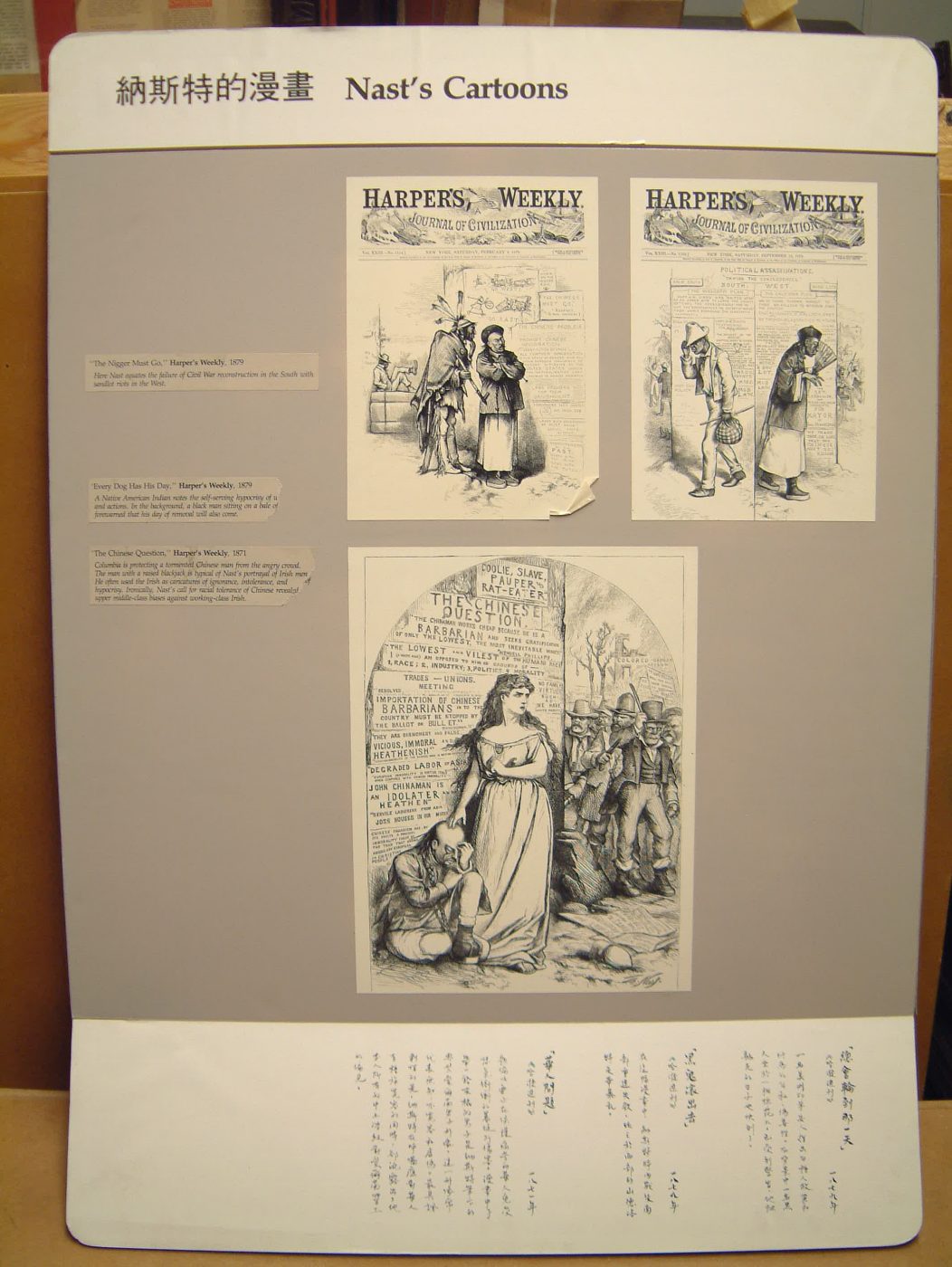

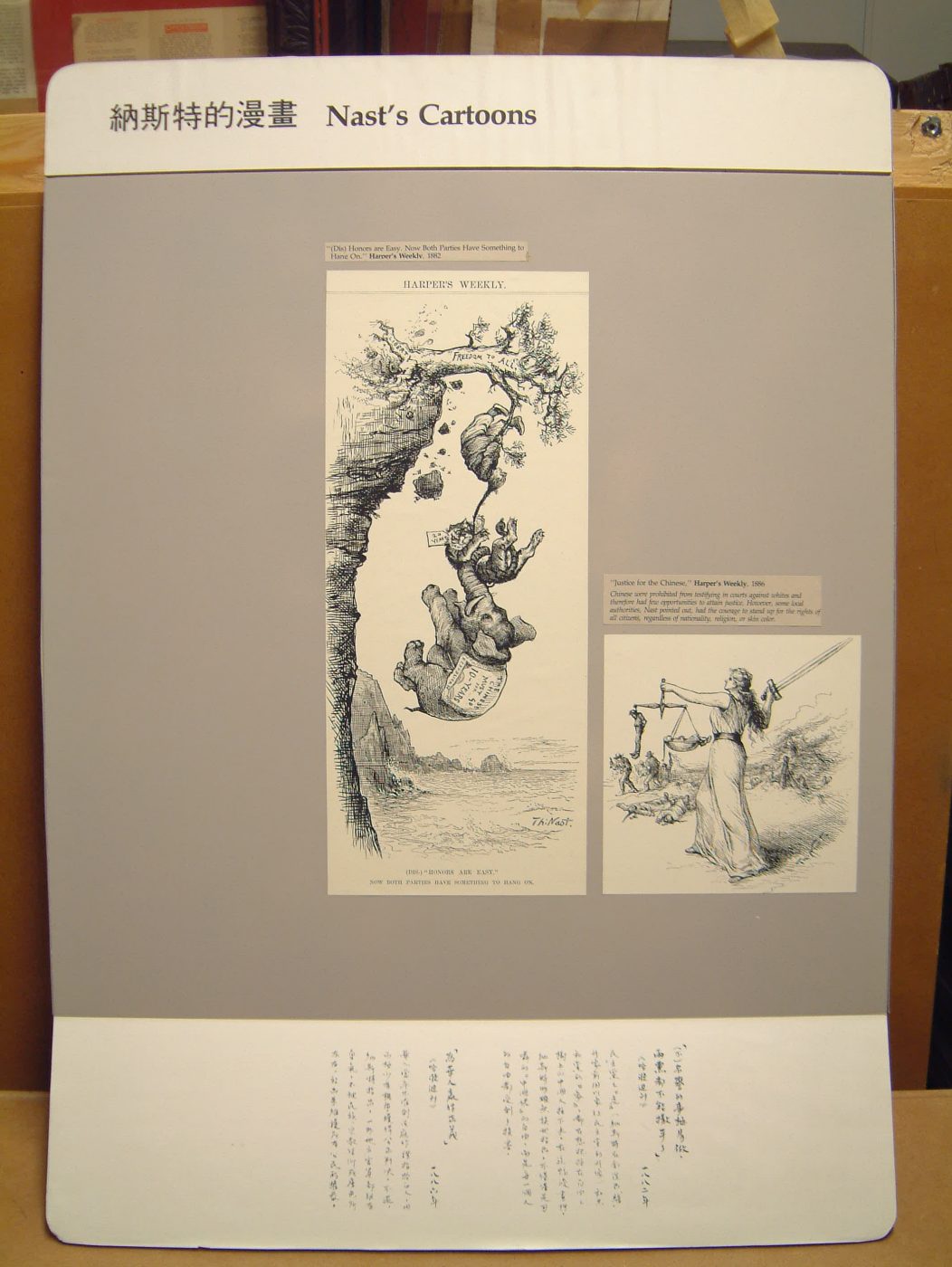

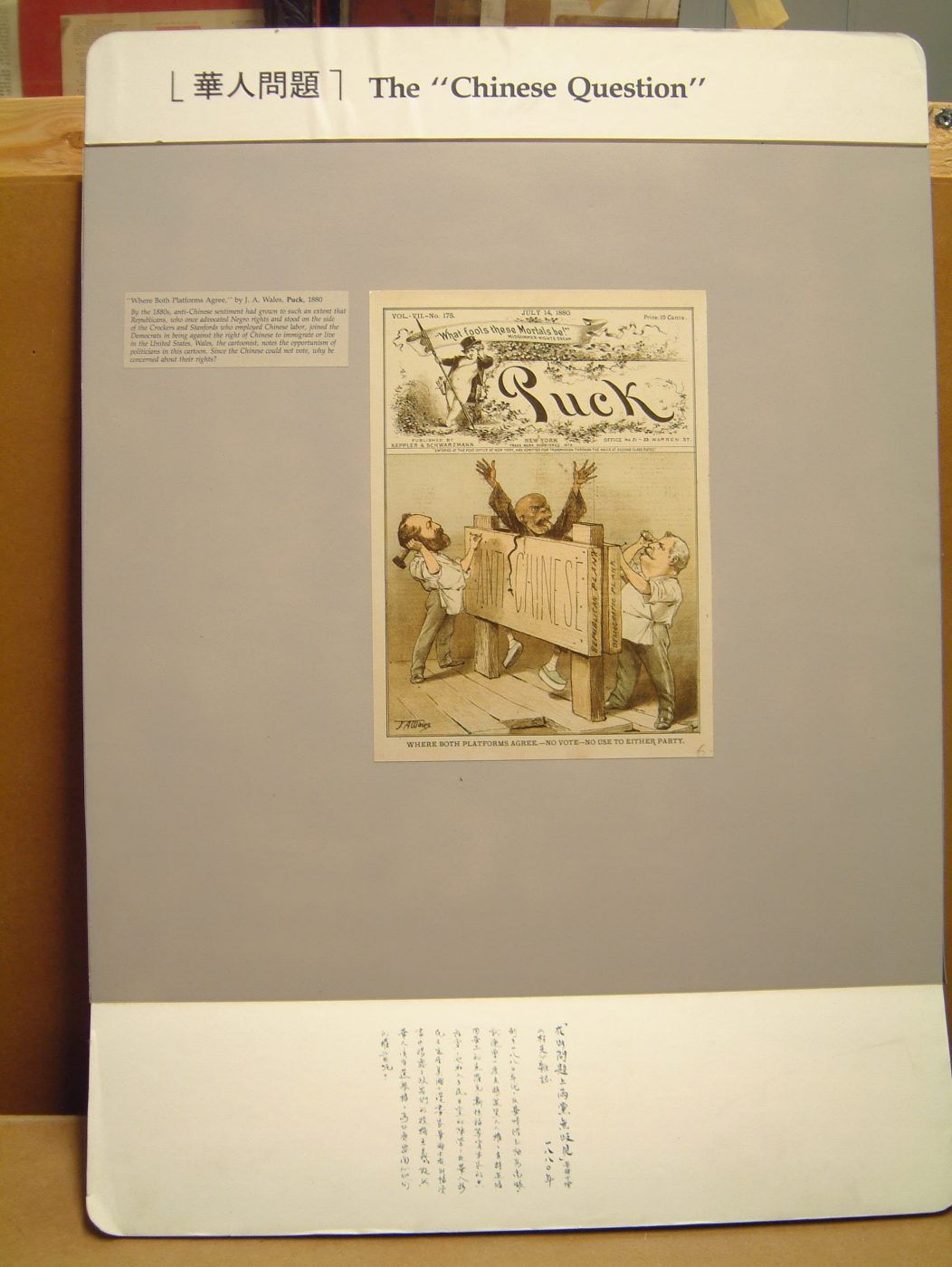

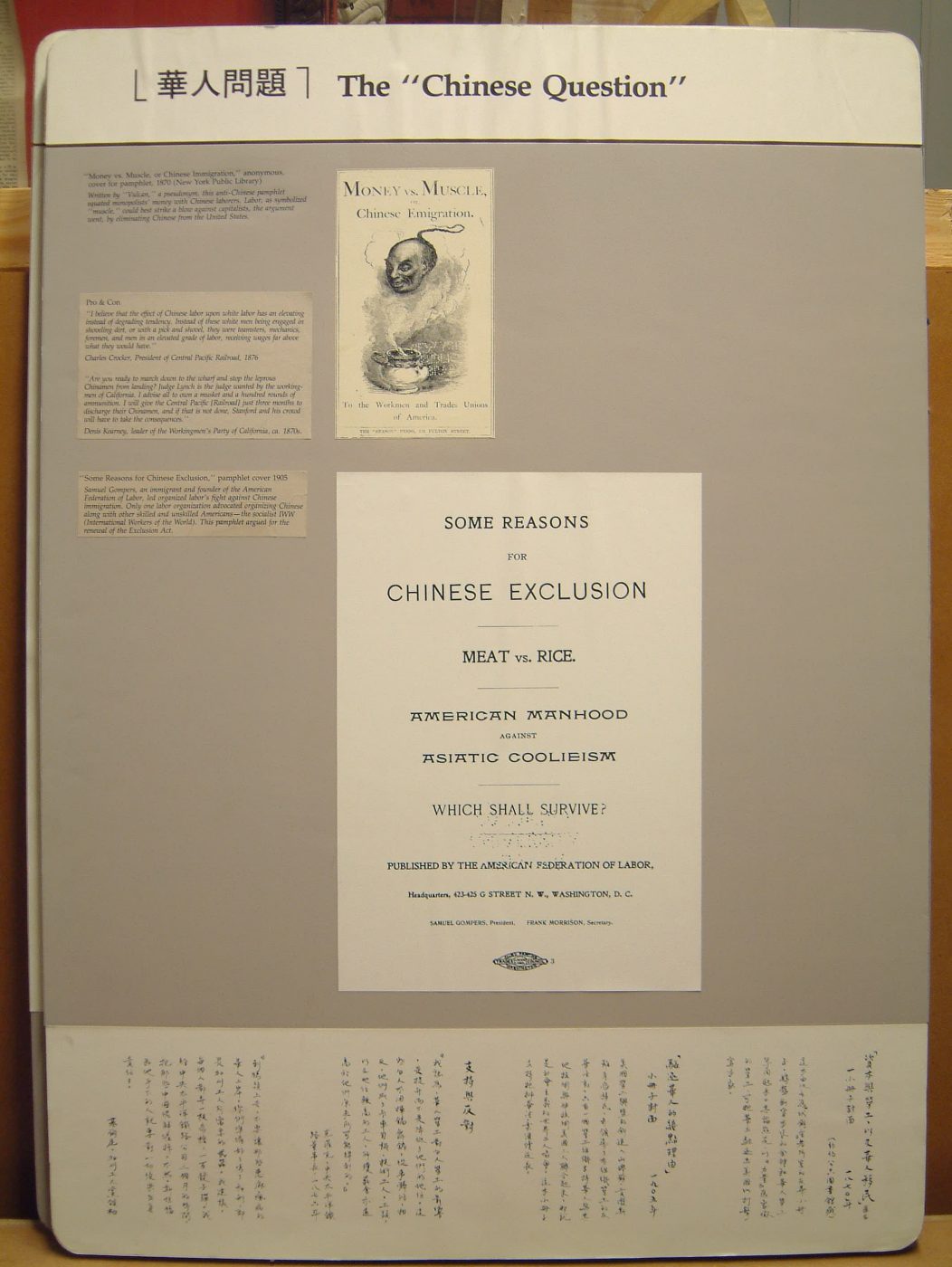

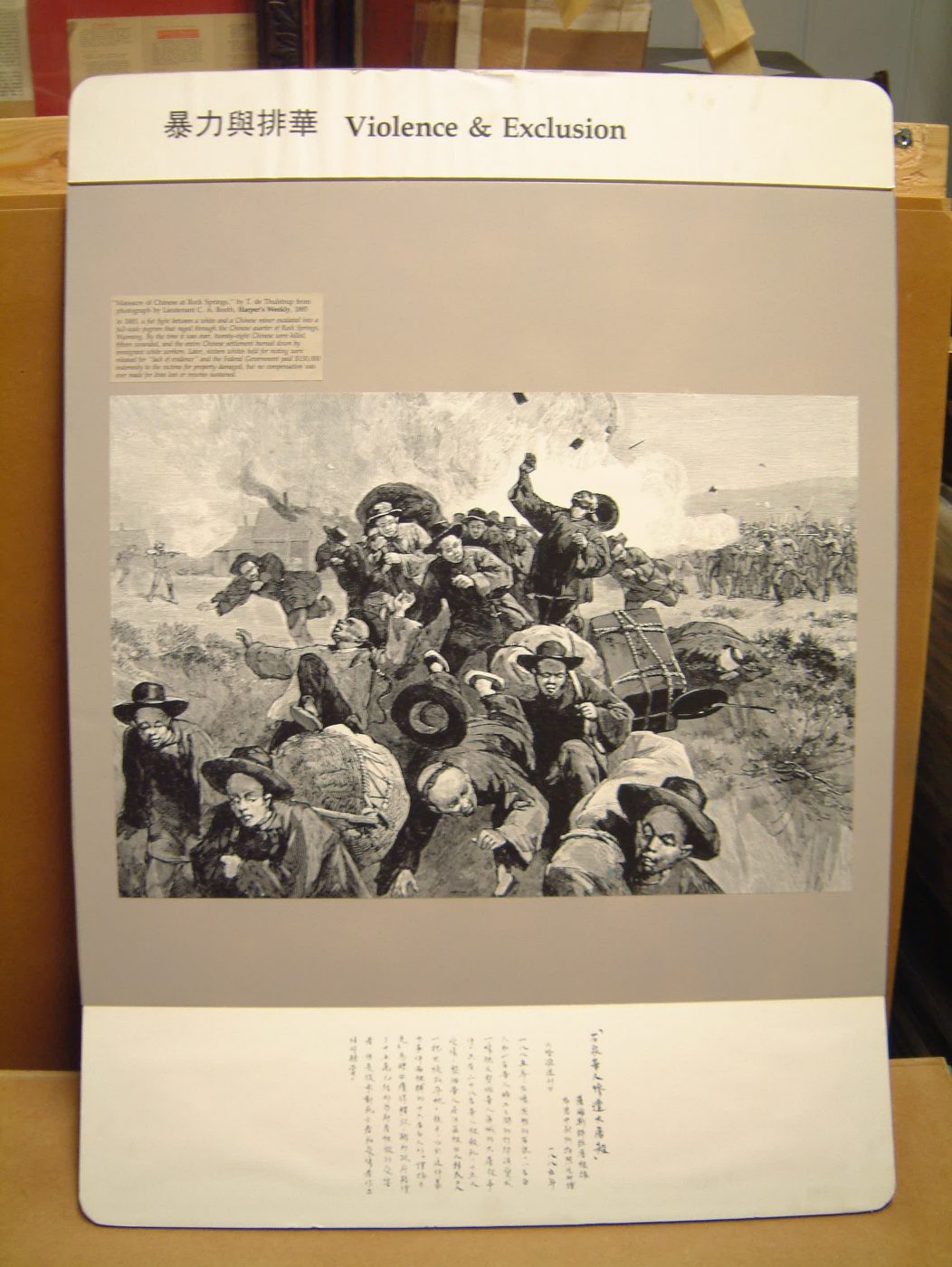

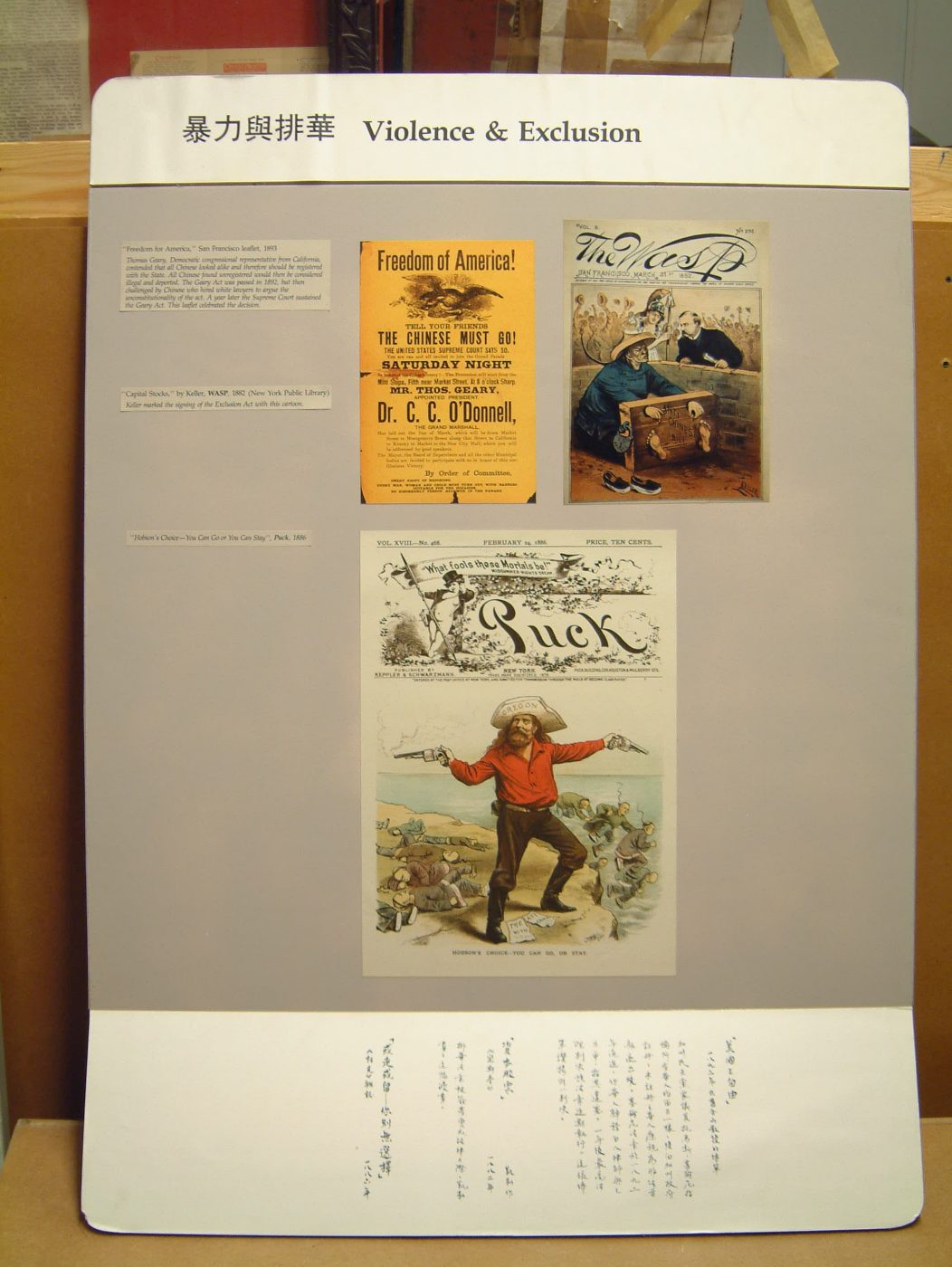

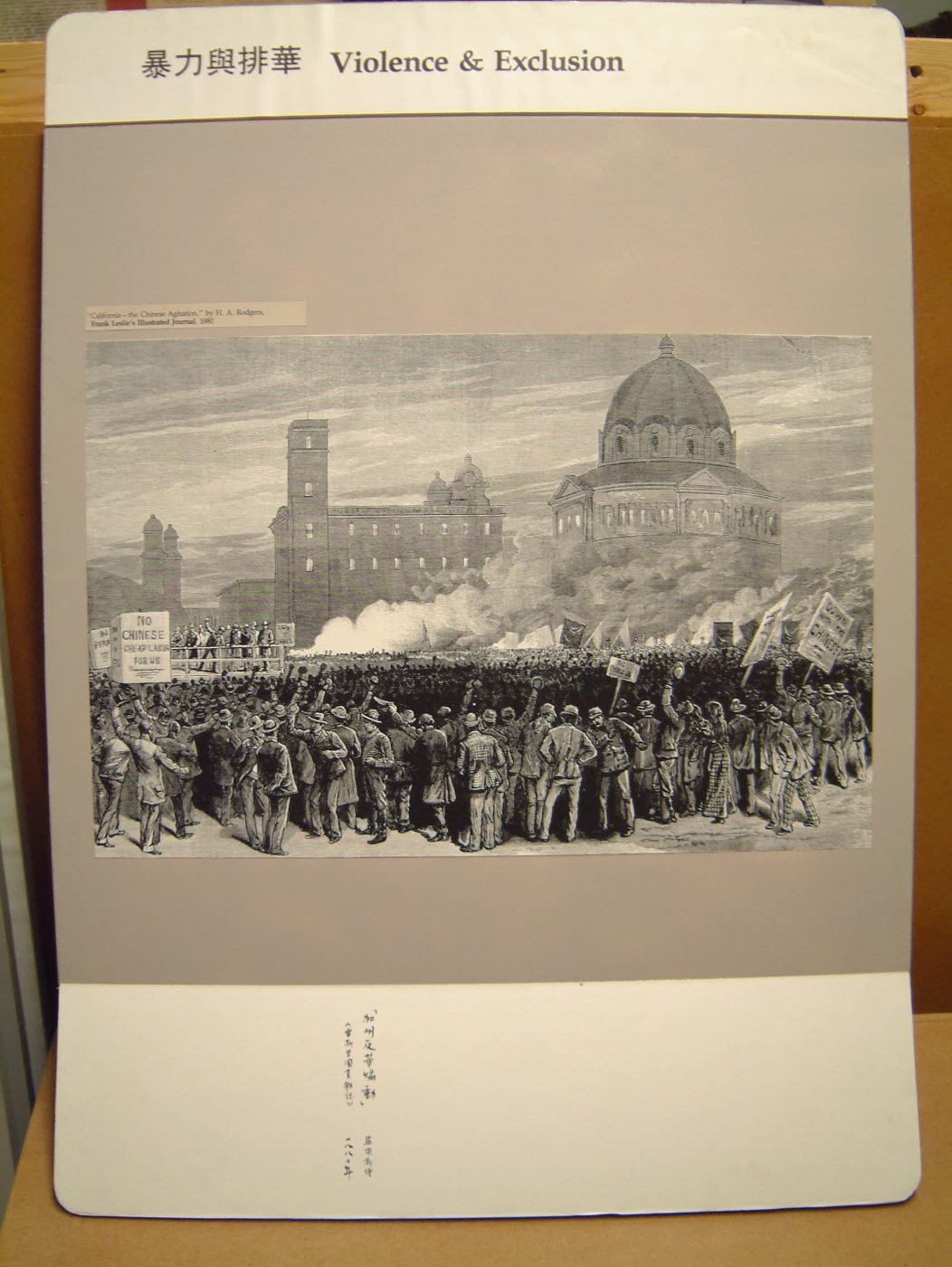

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act became the first law that prohibited individuals from entering the U.S. based on race. In 1986, MOCA developed the exhibition, In the Shadow of Liberty: Graphics of Chinese Exclusion, 1870s – 1890s. The exhibition opening coincided with the 100th year celebration of the Statue of Liberty. Thus, the name of the show critiques the 1886 opening of the Statue of Liberty, a mask of freedom in the United States, while Chinese Americans experienced overt exclusion. In the same year, the New York Times developed a piece called, “Why Asian Students Excel,” bringing attention to a new way of perceiving Asian Americans: the model minority myth. Throughout these events, MOCA strived to ask, “How do we want to gain our liberty? Through exclusion of some or inclusion of all?”

Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏

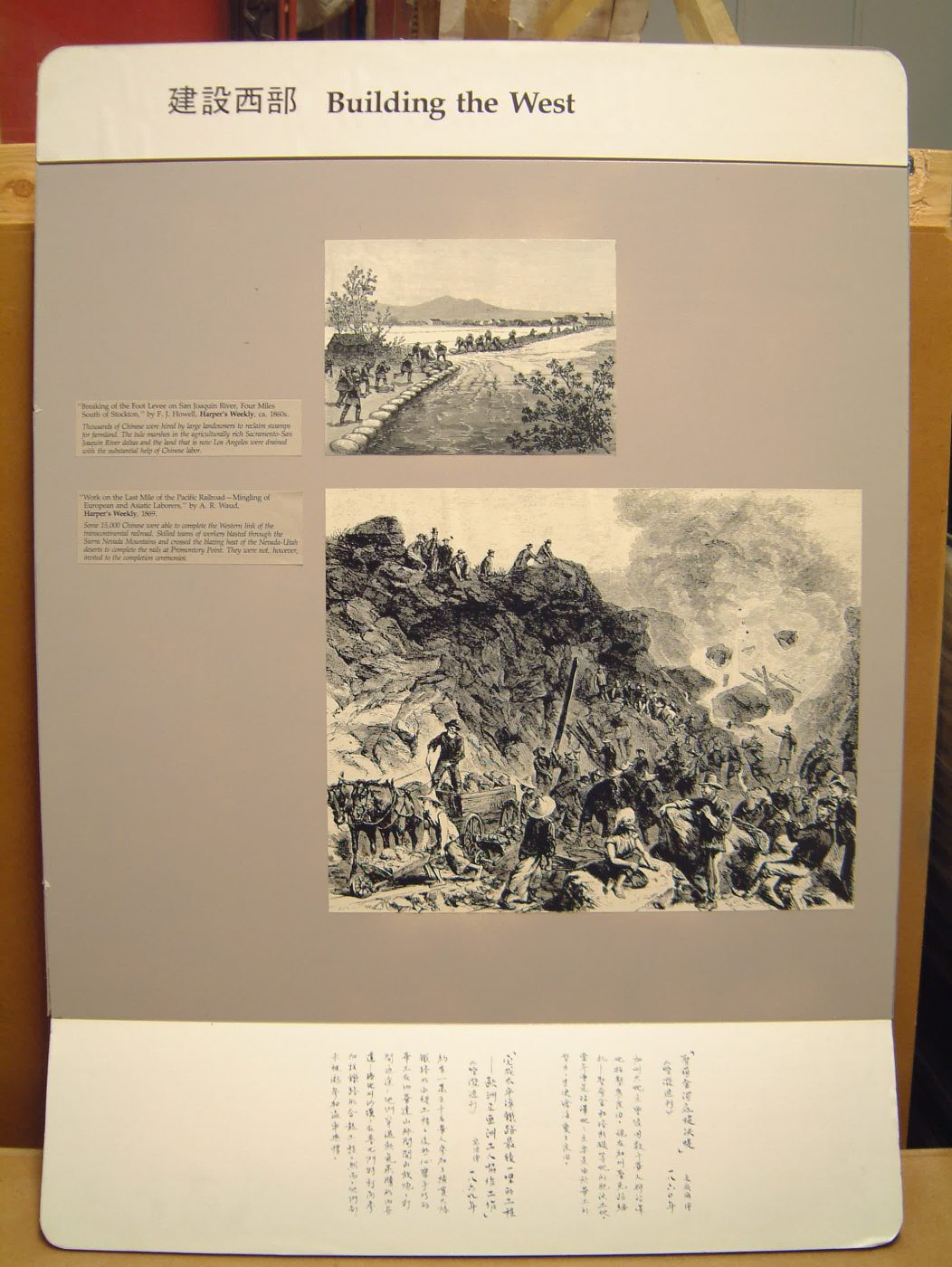

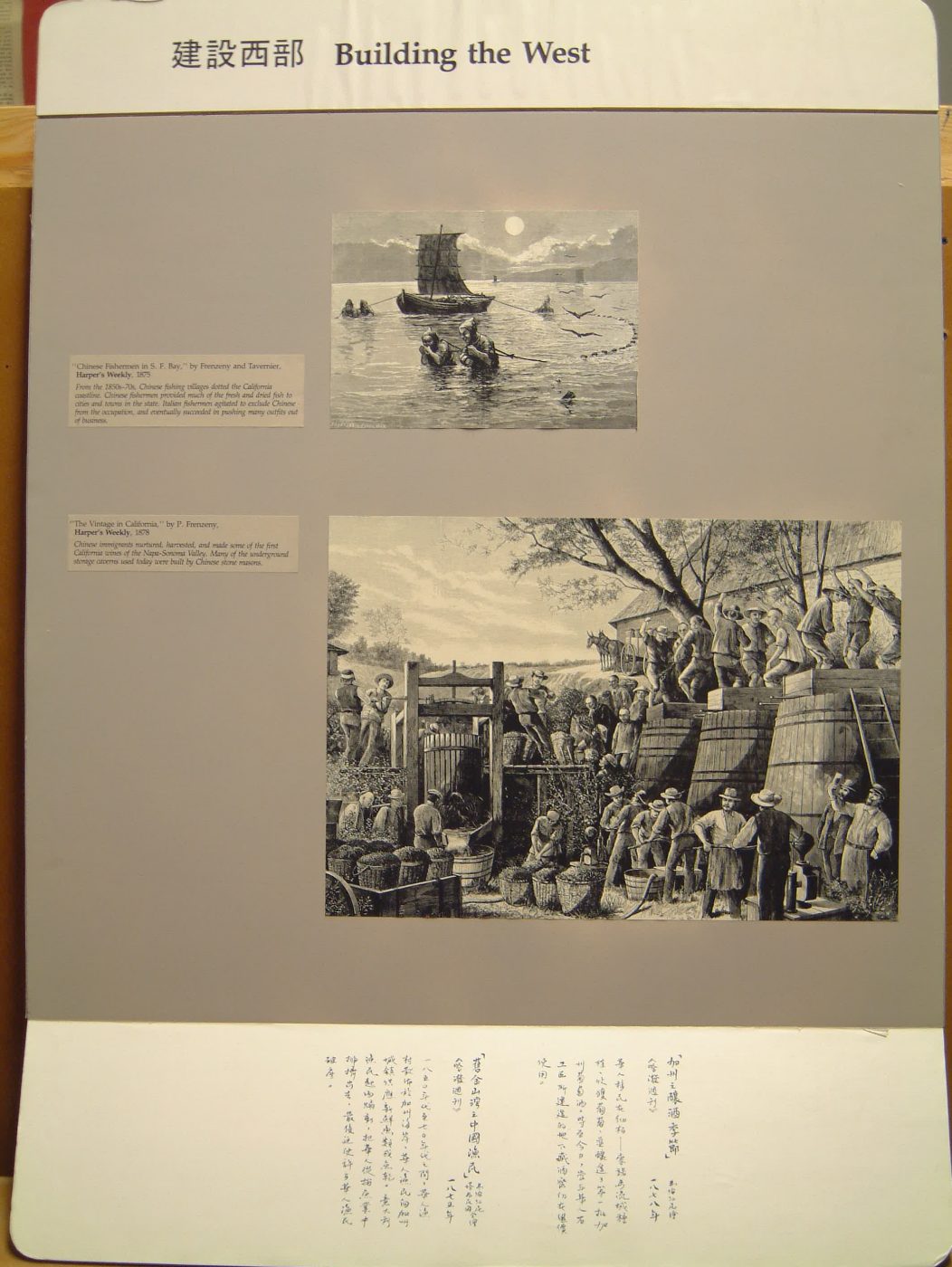

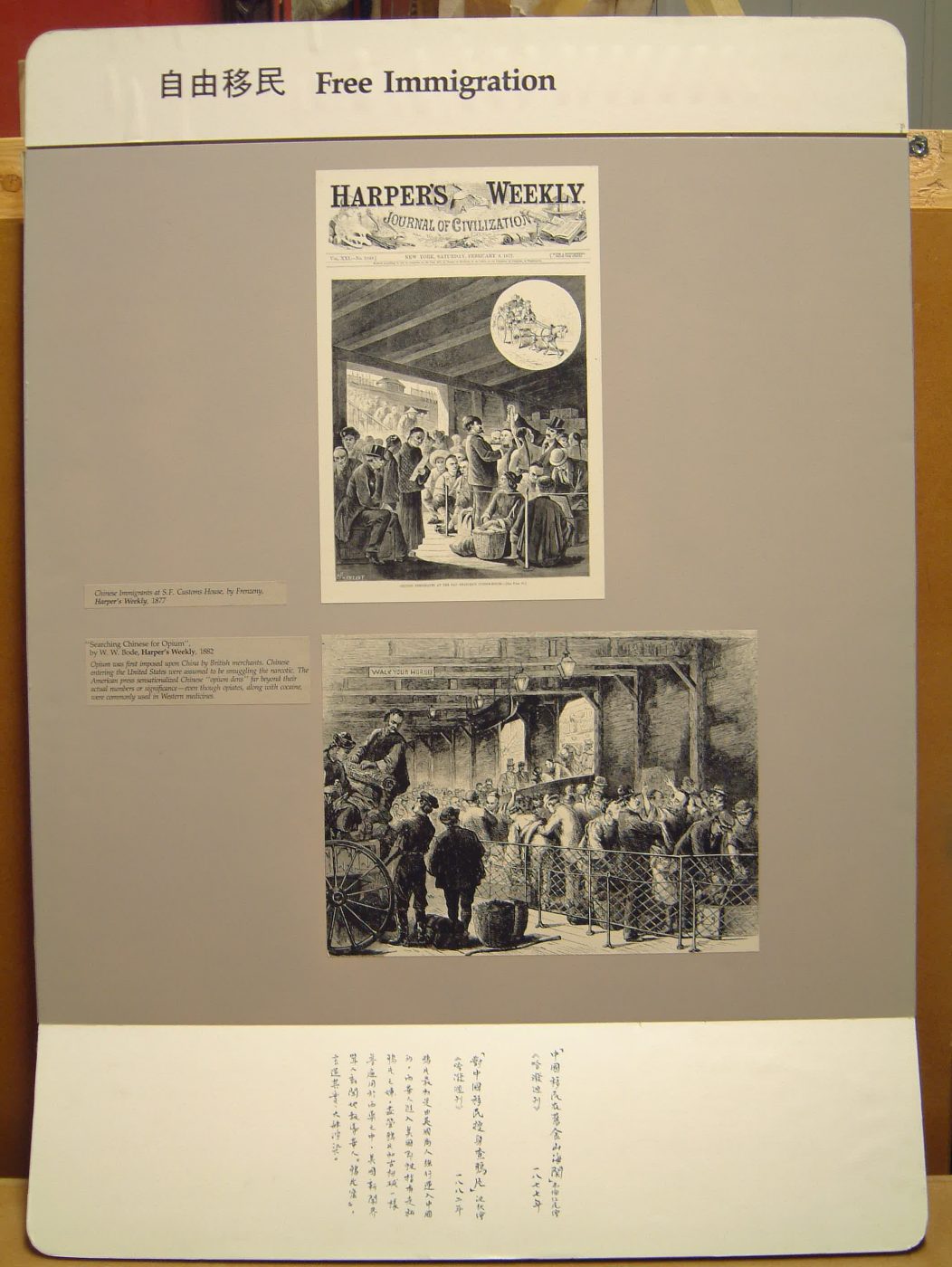

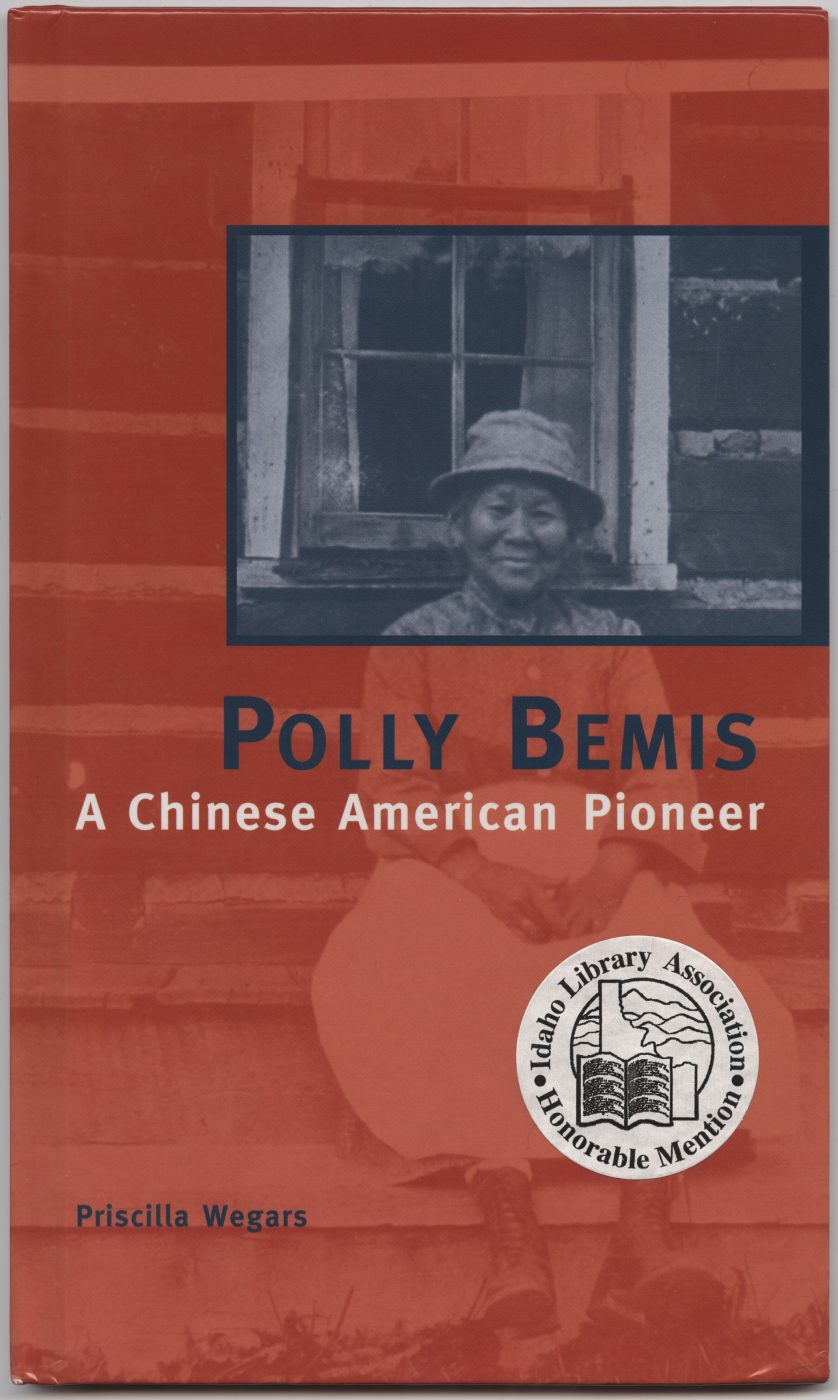

In the Shadow of Liberty, Graphics of Chinese Exclusion, 1870s – 1890s, 1986