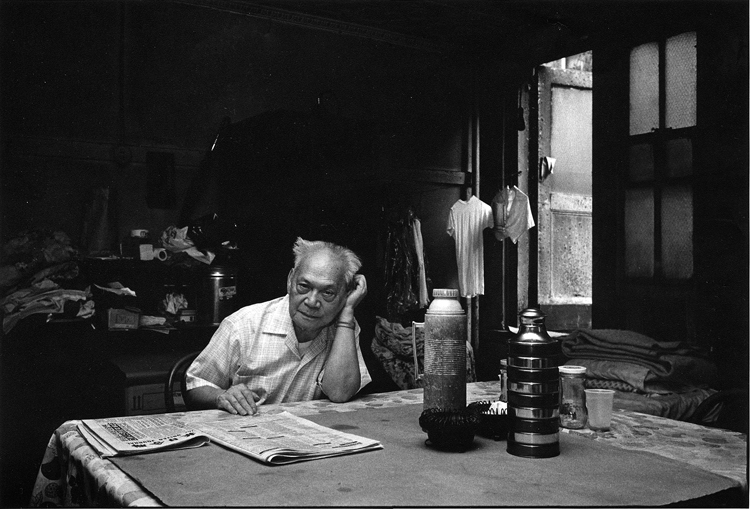

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred the immigration of “skilled and unskilled” Chinese laborers, but loopholes in the law enabled merchants, students, and diplomats to enter the U.S. Those men who managed to pass immigration restrictions, or who had already been living in America when the Act was passed, were unable to bring their wives and children to the States unless they were merchants or native- born citizens. Moreover, miscegenation laws prohibited racially Chinese Americans from marrying women of other races in California and other laws stripped female citizens of their citizenship if they married any foreign born man in order to further discouraged interracial marriages on both fronts. Thus, during the period of Exclusion, Chinese communities in the U.S. became predominantly male “bachelor societies,” where the ratio of men to women rose as high as 27:1. Male laborers shared “bachelor apartments,” a practice which continued long after Exclusion ended in 1943. In this photograph taken by Robert Glick in 1982, an elderly man reads the newspaper at his bachelor apartment on Bayard Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏Collections馆藏

Bachelor Apartments

10 April 2019 Posted.

A man reading the newspaper at a Bachelor Apartment.

Photograph taken by Bud Glick, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Collection.

一位老人在他的单身汉公寓里看报纸。Bud Glick拍摄,美国华人博物馆(MOCA)馆藏