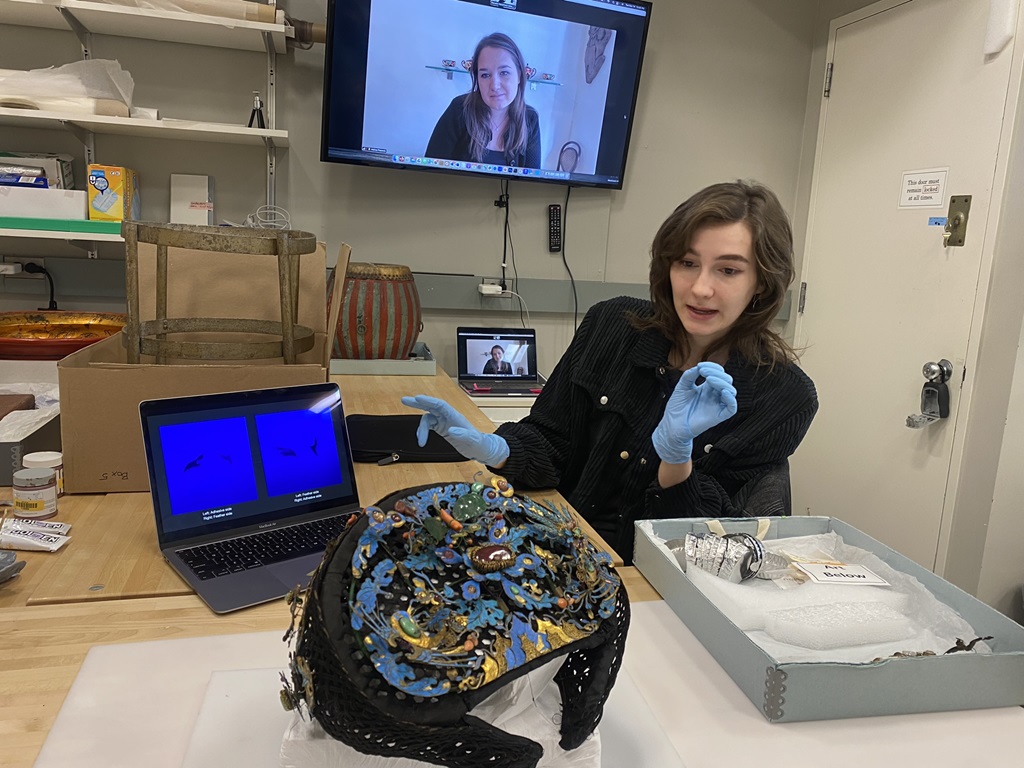

In the fall of 2023, a fruitful collaboration between MOCA and the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, led to a number of objects from the MOCA collections receiving technical analysis and conservation treatment by four NYU graduate conservation students. Devon Lee, a current third-year objects conservation student at the Conservation Center, had the opportunity to investigate and bring new life to this ornate headdress (Vibi Beck Collection, 2003.025.002).

Conservation Treatment of a Tian-Tsui Headdress from the MOCA Collections, by Devon Lee

The headdress, accessioned by MOCA in 2003 with no history of condition or provenance, is constructed in the style of a dianzi (鈿子), a resplendent, horseshoe-shaped headdress that was worn by wealthy Manchu women in the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912) for celebratory events such as weddings and birthdays.

A framework of black silk-wrapped woven rattan cane supports dozens of gilt openwork and filigree ornaments of alloyed copper and silver. These ornaments are suspended on the ends of wires that allow the ornaments to quiver as the wearer moves, creating an effect known as en tremblant. The ornaments contain inset cabochons of semi-precious stones, glass, and red coral, and they are further decorated with tian-tsui (or diancui, literally “dotting with kingfishers”), an ancient Chinese decorative tradition related to cloisonné enameling that utilizes the cut feathers of kingfishers to create striking inlaid motifs in various shades of blue.

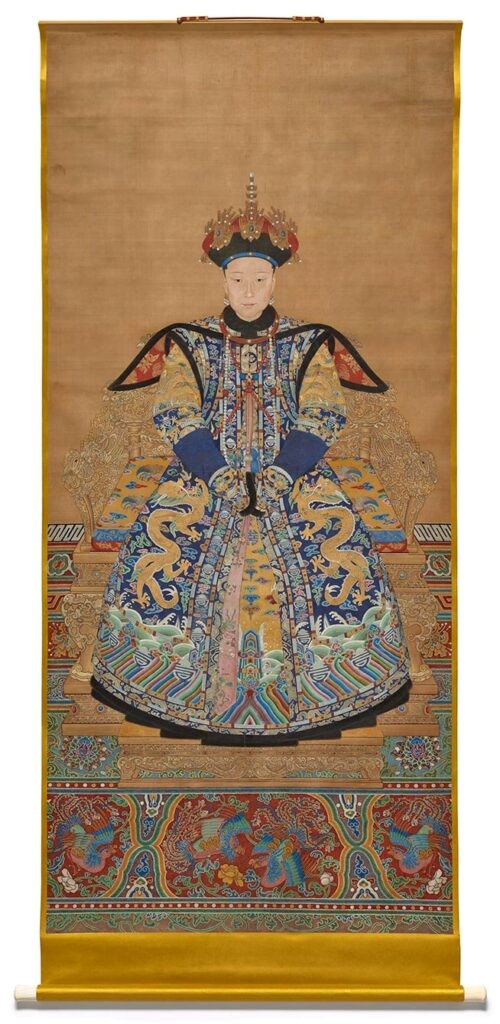

This 18th-century painted scroll illustrates how this type of headdress was worn by women in the imperial court of the Qing Dynasty:

In the traditional manufacture of 19th-century Qing Dynasty tian-tsui headdresses, hairpins, and jewelry, kingfisher feathers were trimmed and inlaid by craftsmen onto ornaments of gilt copper, silver, or paper with a natural adhesive or blend of natural adhesives, including proteinaceous (such as isinglass, which is glue derived from the swim bladders of sturgeon), or plant-based (such as funori, which is a seaweed-derived adhesive). Using a spectroscopic analytical technique, Devon investigated the original adhesive used to apply the kingfisher feathers to the MOCA headdress and found that the adhesive is closely related to reference spectra of proteinaceous and plant-based adhesives; this indicates that the inlay was achieved using traditional methods and materials. As informed by a suite of technical analyses as well as stylistic similarities to comparanda, an attribution of 19th-century Qing Dynasty has been tentatively determined for the MOCA headdress.

The headdress was brought to the Conservation Center for treatment to address a number of condition issues, the most pressing of which was the failure of the original adhesive that had resulted in instability, delamination, and outright loss of the kingfisher feather inlay. A second and equally critical issue was that many of the gilt ornaments had become crushed and deformed, no longer able to tremble with movement of the headdress.

Devon performed consolidation of the kingfisher feather inlay using a combination of conservation-grade adhesives that provided a strong bond to the metal ornaments without affecting the color or surface quality of the kingfisher feathers. As she consolidated the feathers, Devon kept track of her progress with an ornament labeling system and a 50% opacity layer on Photoshop.

As she consolidated the feathers, Devon gently reshaped the deformed floral motifs throughout the metal ornaments, carefully restoring their three-dimensionality and ability to tremble on the ends of their thin wires.

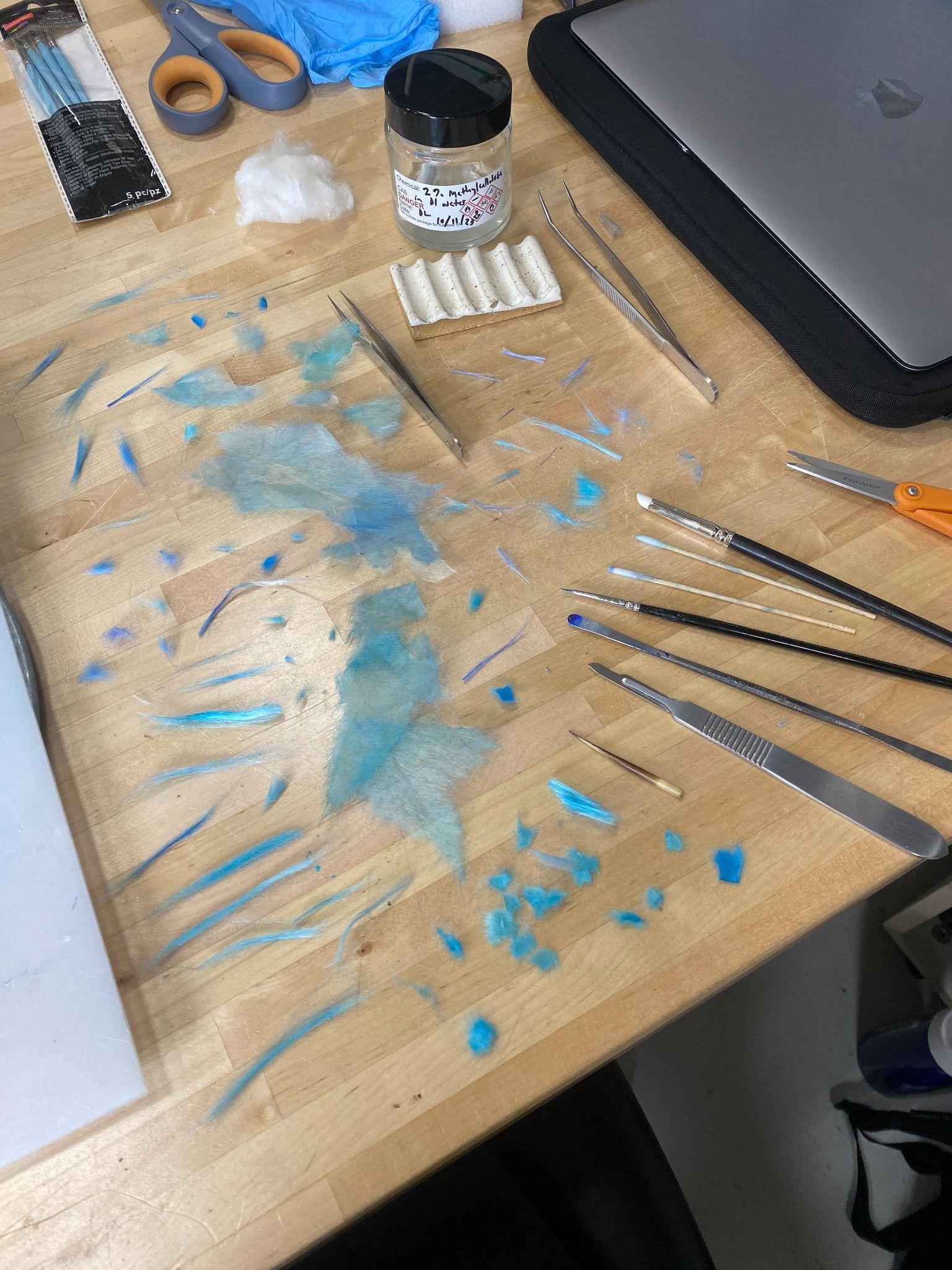

After the tian-tsui decoration was stabilized, it was time to reattach the detached feather pieces, cabochons, and the wings of the phoenix on ornament 18 to reintegrate the original materials of the headdress and mitigate the possibility of their dissociation from the headdress in the future. Devon laid out all of the detached kingfisher feather pieces and, using a conservation-grade adhesive, began to reattach them to their original ornaments throughout the headdress based on their size, color, and shape.

With the detached feather pieces, cabochons, and the wings of the phoenix reattached, the headdress was finally clean and structurally sound, and the viability of further conservation intervention could be evaluated.

The extant original kingfisher feather pieces far outnumbered the areas of gilt metal exposed by loss of the tian-tsui inlay, and in discussion with MOCA staff, it was determined that cosmetic loss compensation for the missing kingfisher feather inlay would better reflect what the headdress would have looked like when it was in active use. Though it is a highly interventive conservation step that serves to somewhat obscure the long life and deterioration of the headdress, compensation for the lost tian-tsui decoration was deemed an acceptable measure for an object with such high aesthetic and cultural value.

Because the global population of kingfishers is threatened by climate change and overexploitation, Devon felt that it would be inappropriate to use even ethically sourced kingfisher feathers to fill the areas of loss throughout the headdress and she set out to identify more sustainable materials for this treatment. After experimenting with a number of materials to find the best match for the color and surface qualities of kingfisher feathers, Devon began to craft imitation tian-tsui decoration from highly renewable natural plant fibers colored with conservation-grade dyes.

To add one final layer of complexity to this treatment, the color of kingfisher feathers is structural in nature, rather than the product of biopigmentation. The blue color of kingfisher feathers is produced through physical scattering of light through the spongy keratin structure of the feather, meaning that when kingfisher feathers are viewed in different lighting conditions or from different angles, we may perceive a change in their color. The nature of structurally colored feathers complicates loss compensation, because the color of an imitation feather is fixed and static, whereas the perceived color of the true kingfisher feather can shift.

The dyed plant fibers were adhered in narrow strips over the areas of loss in the same orientation as the extant feather pieces or as indicated by parallel lines of residue from the original adhesive. Devon’s course of action was to tone her imitation feathers to match the color of the tian-tsui when viewed straight on, as this is the angle from which each ornament will most likely be closely examined on display. When conservators perform loss compensation to a high degree of visual integration, they will sometimes finish a fill with a dot of a colorless material that fluoresces under UV illumination to signal to researchers or future conservators that it is not original material. In the case of this treatment, however, to distinguish the fill materials from the true kingfisher feathers, you need only look at each ornament from the side!

After imitation tian-tsui was applied to all of the exposed gilt metal using a retreatable conservation-grade adhesive, Devon constructed an internal support and mount that can be used for display or long-term storage. After three months of challenging work, the headdress was ready to return to MOCA with much of its vitality returned.