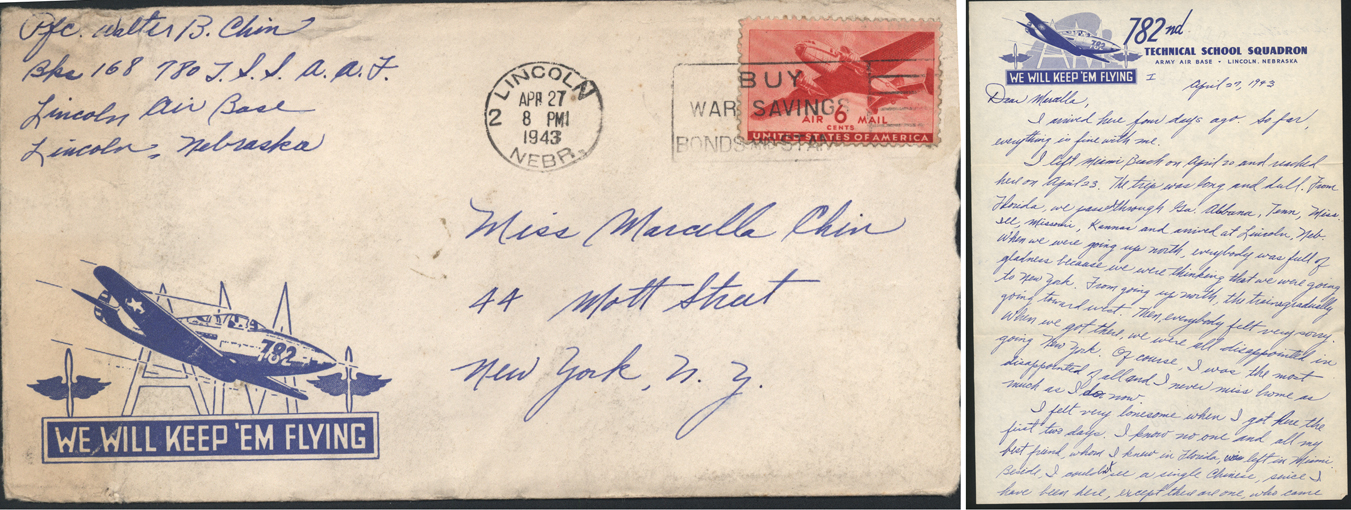

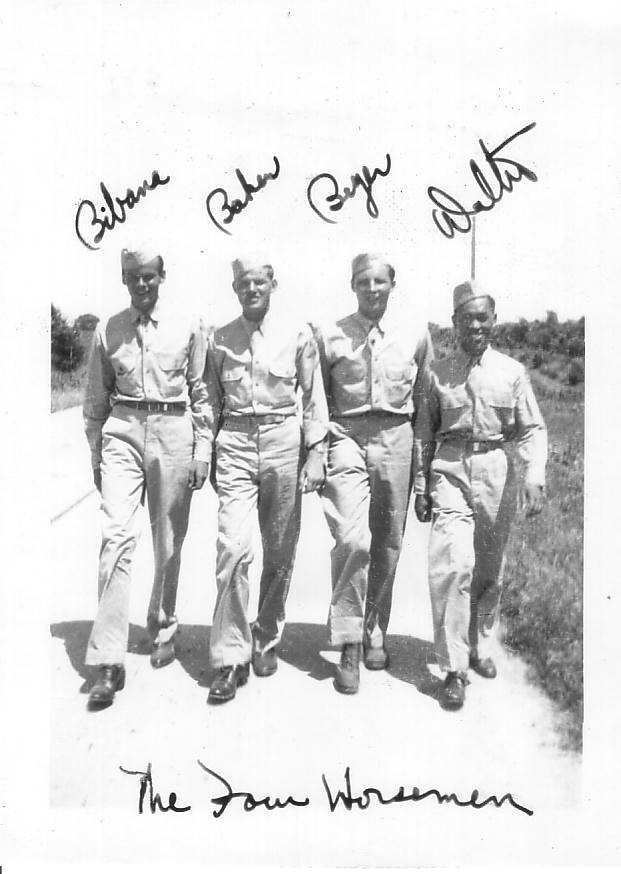

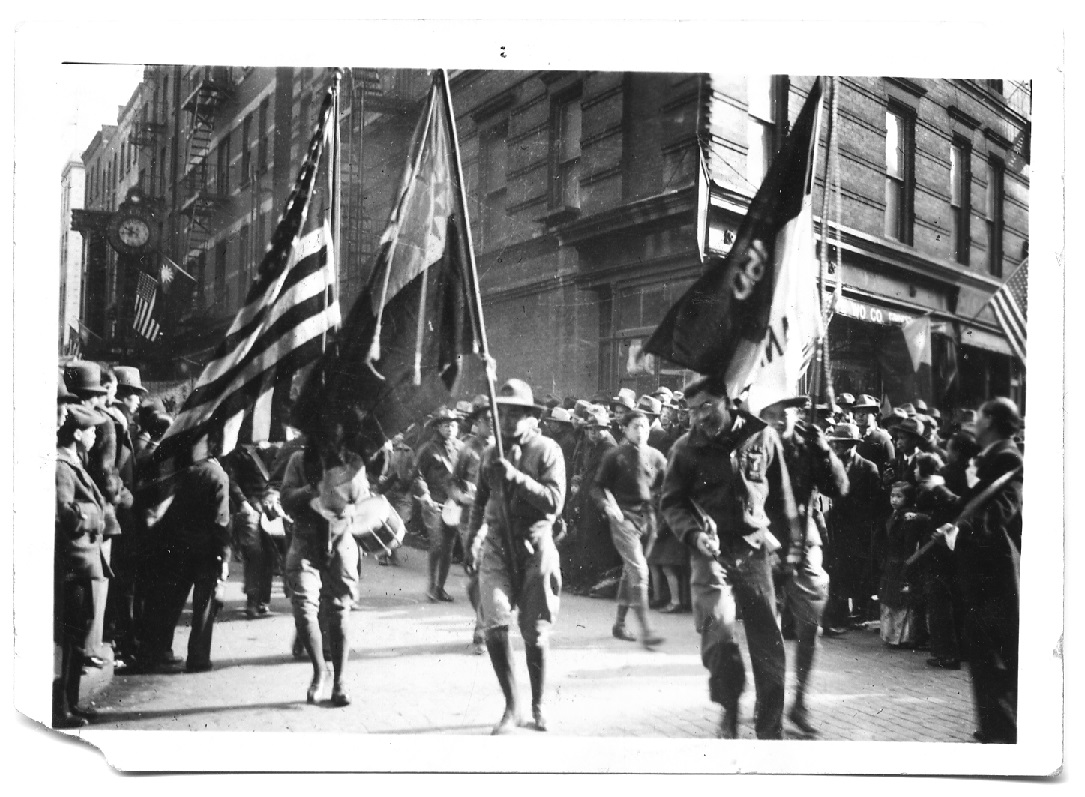

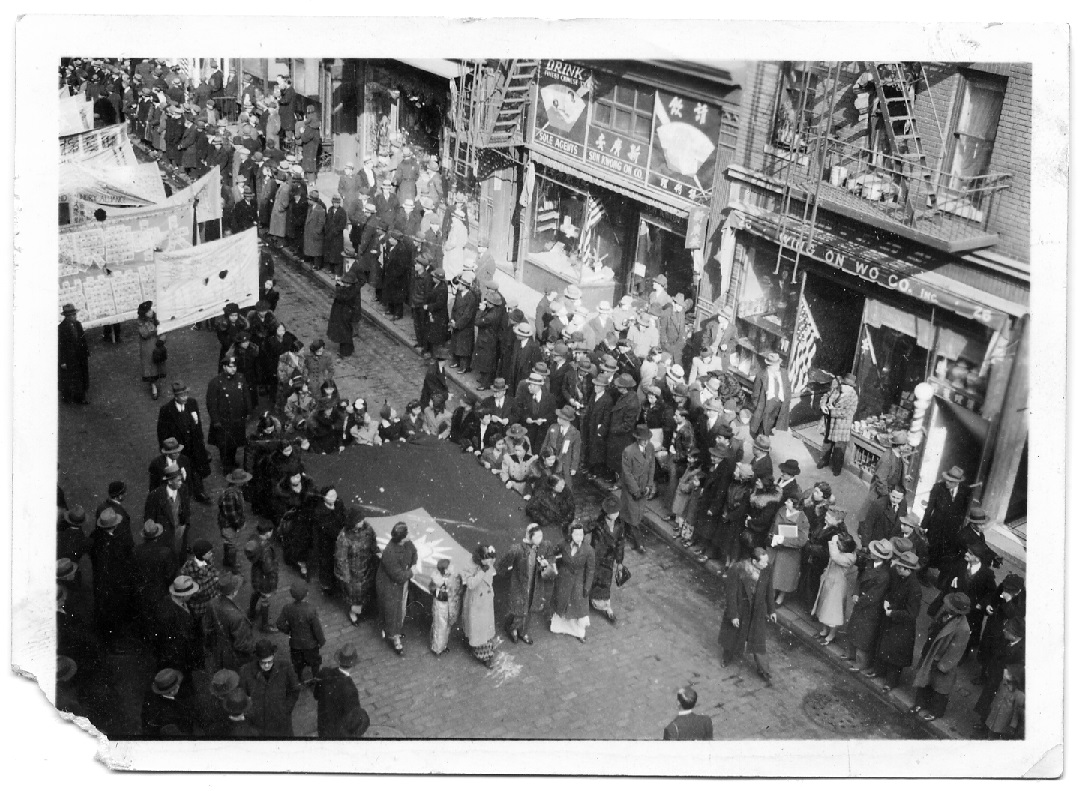

With firsthand details and an earnest tone that drew readers and listeners alike in, the letters recounted the mundane, everyday life in the barracks, basic training, kitchen duty, mosquitos, requests of objects or news from home, encounters with fellow Chinese American soldiers, desire for connection and the familiar, the honor of dying for one’s country, and impressions of new places as their units moved across the U.S.—from Lincoln, NE, Fort Myers, FL, Camp Wheeler, GA, San Francisco, CA, and Seattle, WA—to being deployed to fight at the front overseas.

The audience generally appreciated learning about these experiences, but interestingly, a few found just as compelling the notable silences. Connecting it to the present, an activist who organized around seeking justice for Private Danny Chen, who was racially harassed, teased, bullied, and mercilessly beaten by his fellow soldiers before he committed suicide in 2011, asserted that she could not believe that Chinese American soldiers did not also experience racist treatment in the U.S. military of the 1940s.

This opened up a discussion of what else was left unsaid in the letters—the psychological trauma and weight one must feel when one takes a life, the terror and horrors of war. All this they perhaps left unsaid to spare their families. This turn in the discussion to what was missing inspired an audience member and actor to share with the group what happened to their own families, who lived through the Japanese occupation and war in Shanghai and Hong Kong, respectively. Another contributor to the discussion, a World War II veteran in the audience, spoke from experience that the military did in fact read and censor letters and punished soldiers who displeased the censors with unpleasant duties, perhaps explaining the silences.

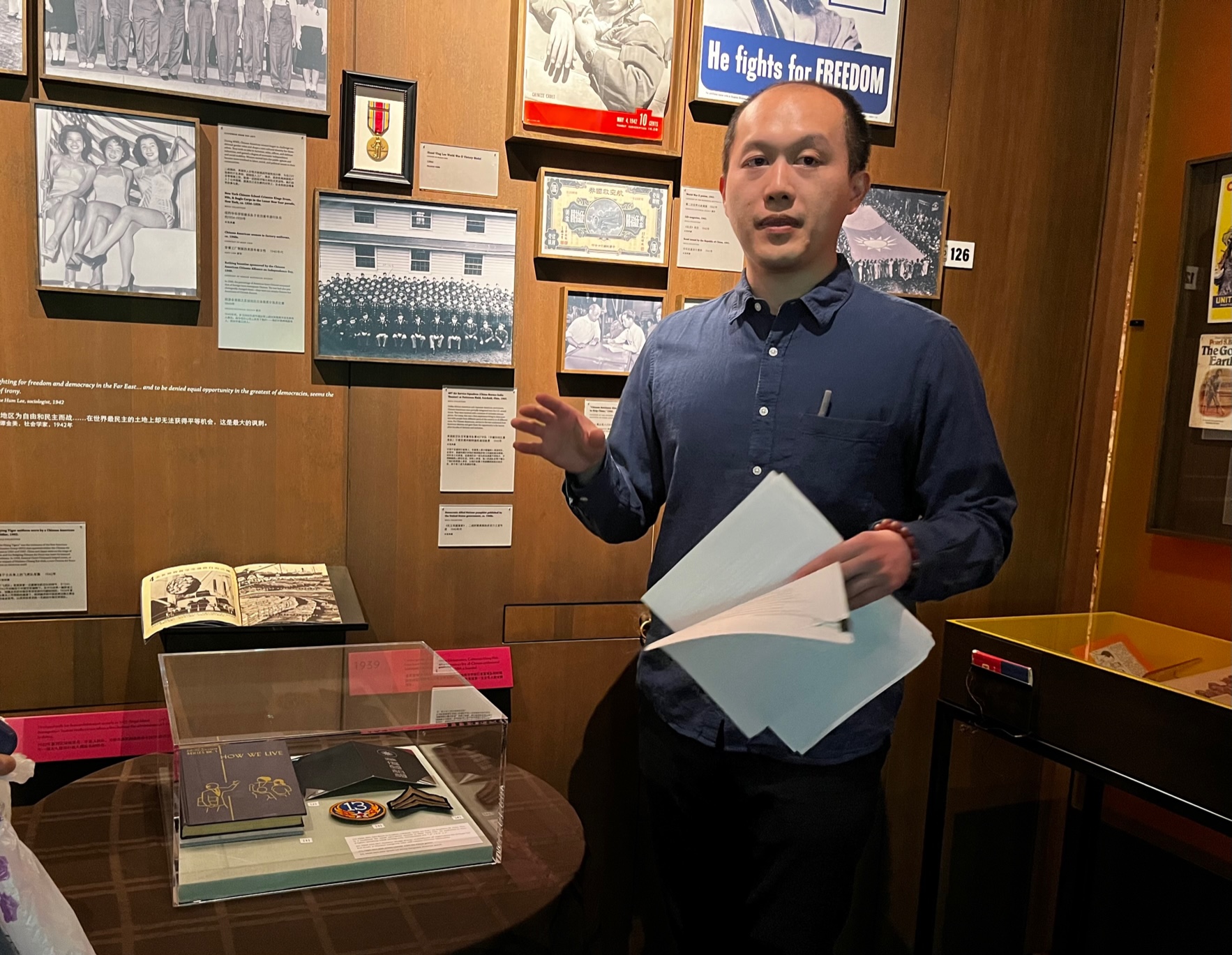

All in all, the performance—replete with storytelling, memory-sharing, and discussion informed by historical photographs, documents, and artifacts from MOCA’s collection—was an educational and entertaining way to spend an evening during AAPI Heritage Month.