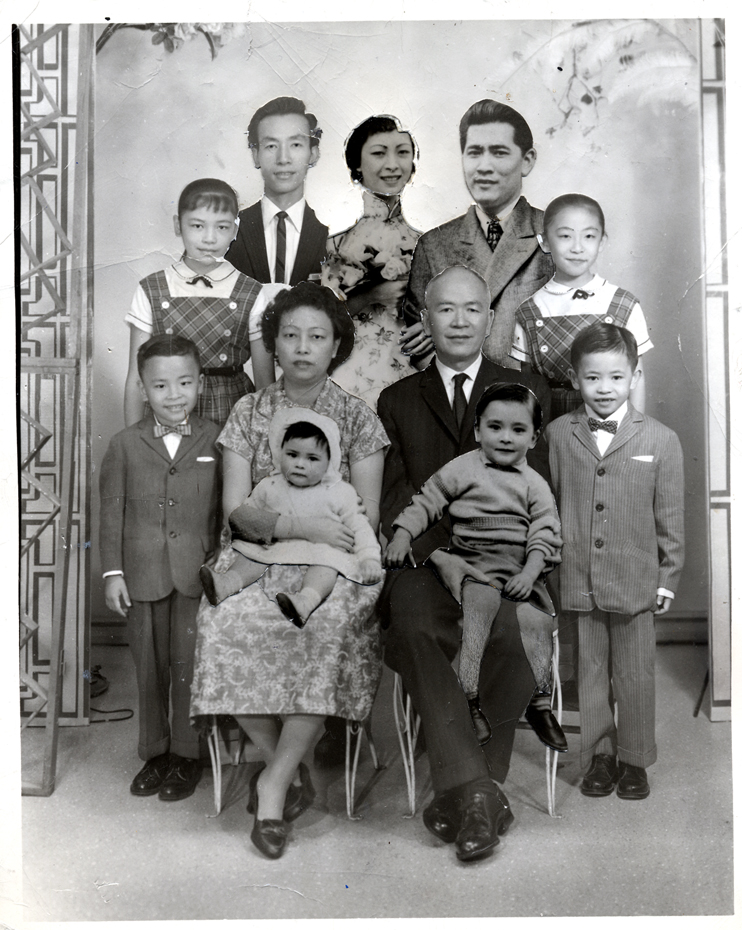

In the above photograph, taken ca. 1961, the seated elderly gentleman is Lin S. Low. Low served in the U.S. Army during World War II, and as result, became a naturalized citizen eligible to sponsor his wife and children, then living in Hong Kong, to join him in the United States. However, due to unsupported documentation, eldest daughter Moo Gee was not allowed to enter. This portrait gives the impression that the whole family was eventually able to reunite, however, the Low family portrait is actually a composite photograph on which the heads of four separated family members—eldest daughter Moo Gee, her husband and two young children—were pasted onto the bodies of stand-ins at the studio where the family went to take the original base portrait. In actuality, after they left Hong Kong, it would be more than twenty years until the Lows would see Moo Gee again. In the intervening years, she had remained in Hong Kong with other relatives and later married Stanley Wong, with whom she relocated to London and started a family.

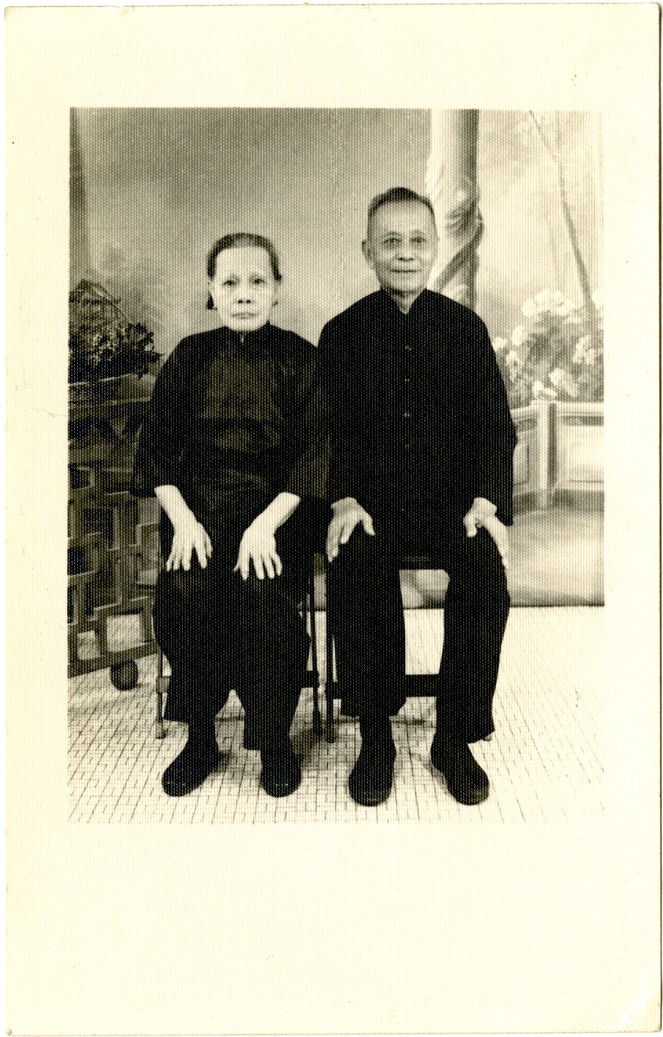

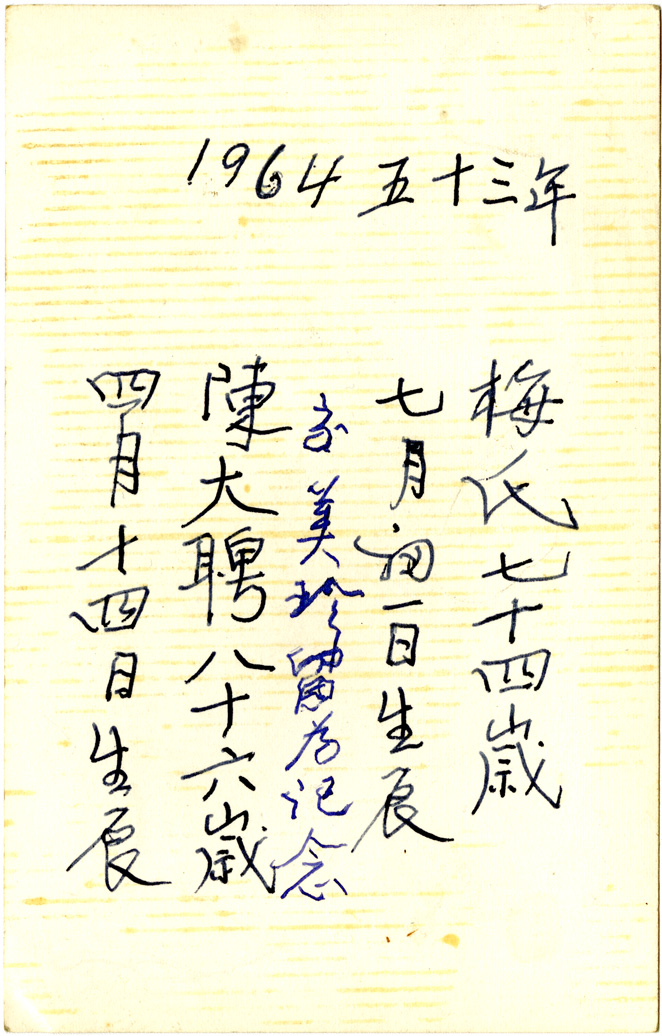

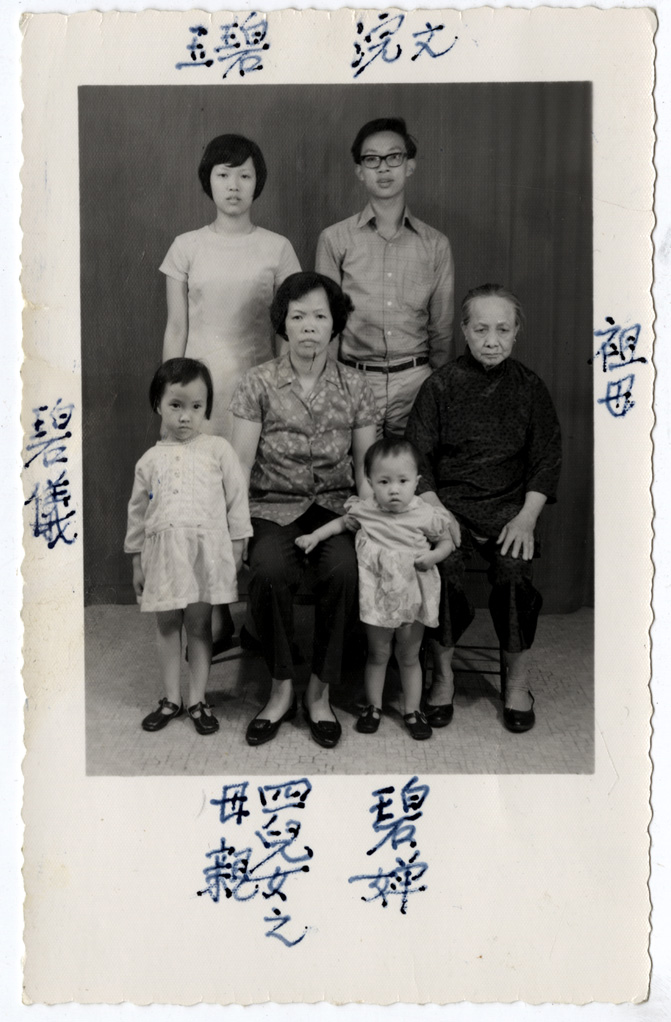

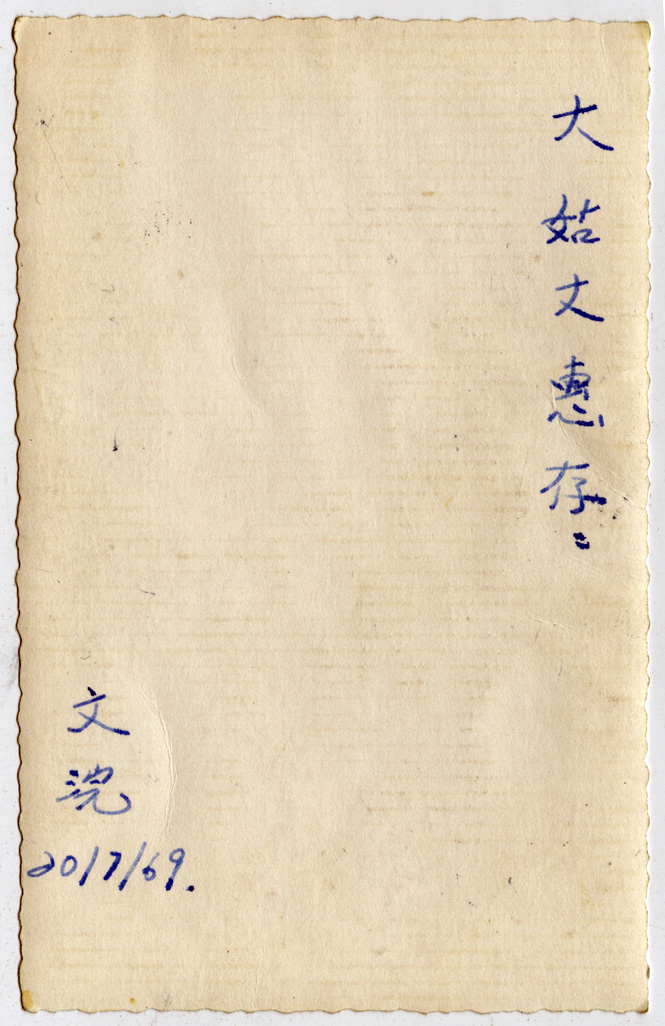

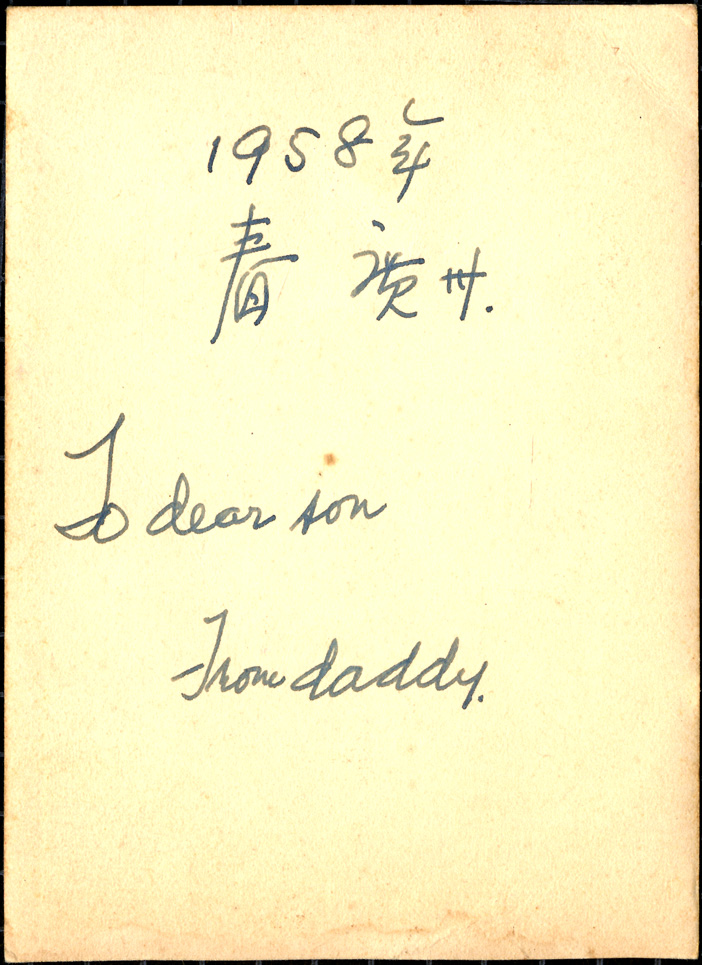

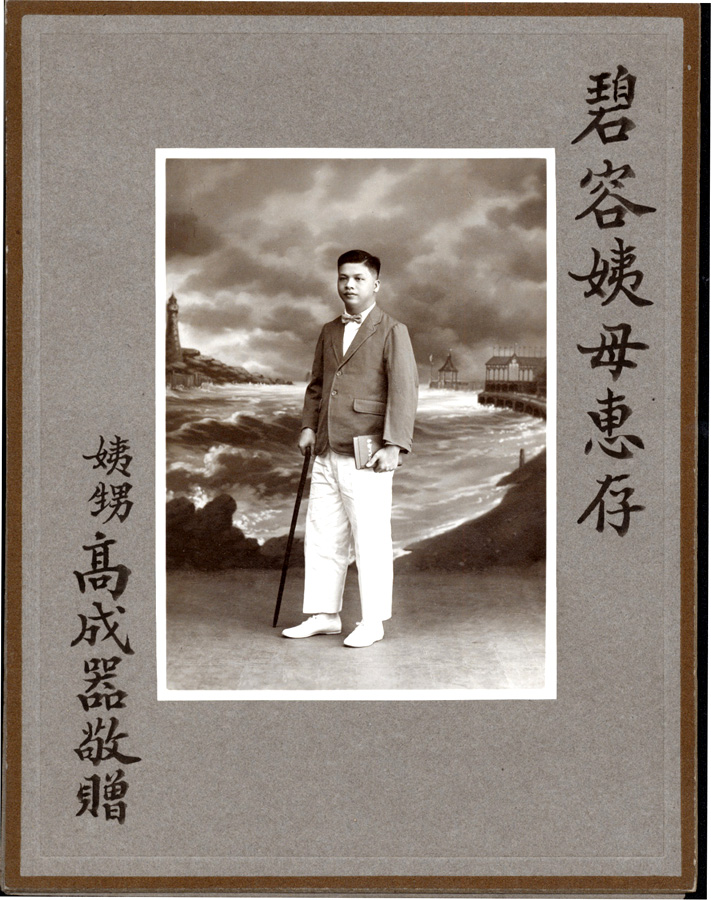

Shaped by a legacy of immigration and exclusion, Chinese American families have been no strangers to extended family separation. Looking through MOCA’s collection of historical portraits, especially ones with handwritten messages addressed to family to whom they were sent, one wonders about both presences and absences. Before Zoom, FaceTime, and Skype cheaply connected people across oceans through video conferencing technology, Chinese leaving home to labor overseas did not expect to see their families for many years. Photographs of loved ones became cherished mementos, taken before emigrating or sent through the mail to accompany updates. And before mass-accessible camera technology, portrait studios served the needs of not only local but also transnational immigrant communities. Before leaving Hong Kong, a primary port of emigration, emigrants visited studios such as that of the prolific Francis Wu and later ones set up by émigré photographers from China after 1949. Little is known about the neighborhood-based photography studios serving NYC’s immigrant Lower East Side and Chinatown, but the stamps printed on the back of portraits or their accompanying paper frame help us identify a handful of them. At various points, Chinese immigrants had their portraits taken at Wellington Lee Studio at 44 Mulberry Street, Tarsy Photo Studio at 8 Catherine Street, Jon Yon Photo Studio at 62-64 Bayard Street, Natural Photo Studio (天然影相馆) at 47 Mott Street, and many long forgotten others. Studies of other immigrant-sending communities have found family albums filled with photographs stamped with portrait studio addresses located in immigrant-receiving communities in the United States. They are a testament to enduring family bonds but also long separations necessitated by transnational migration.