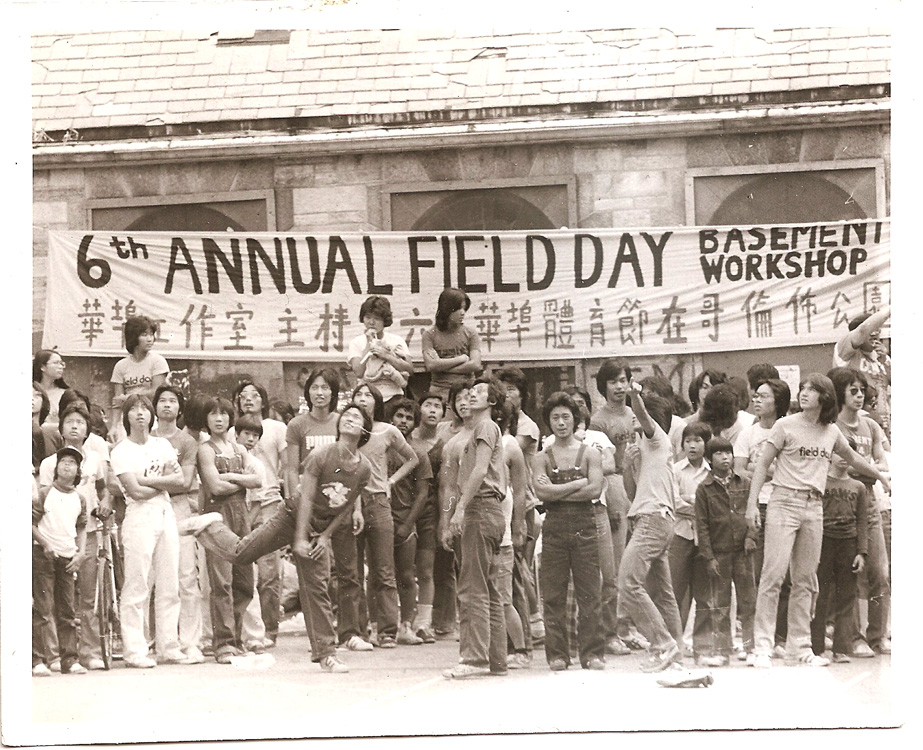

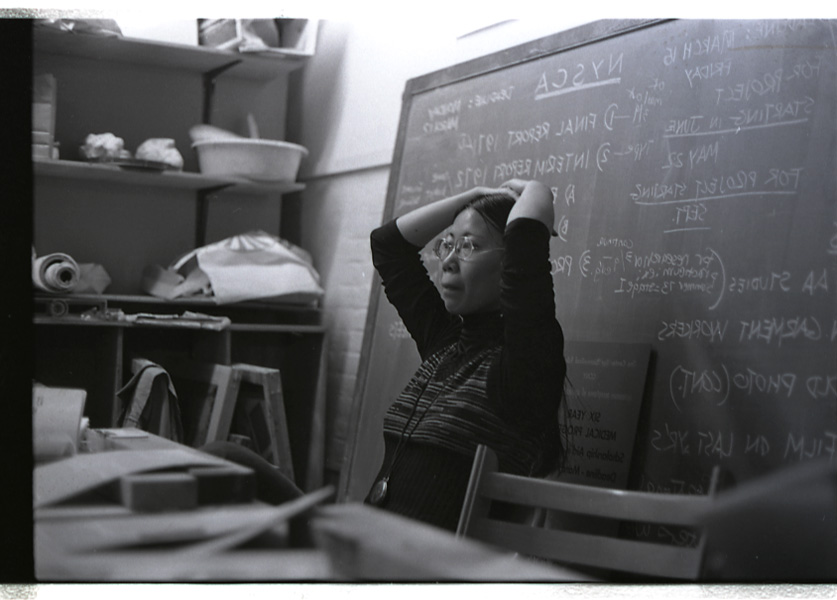

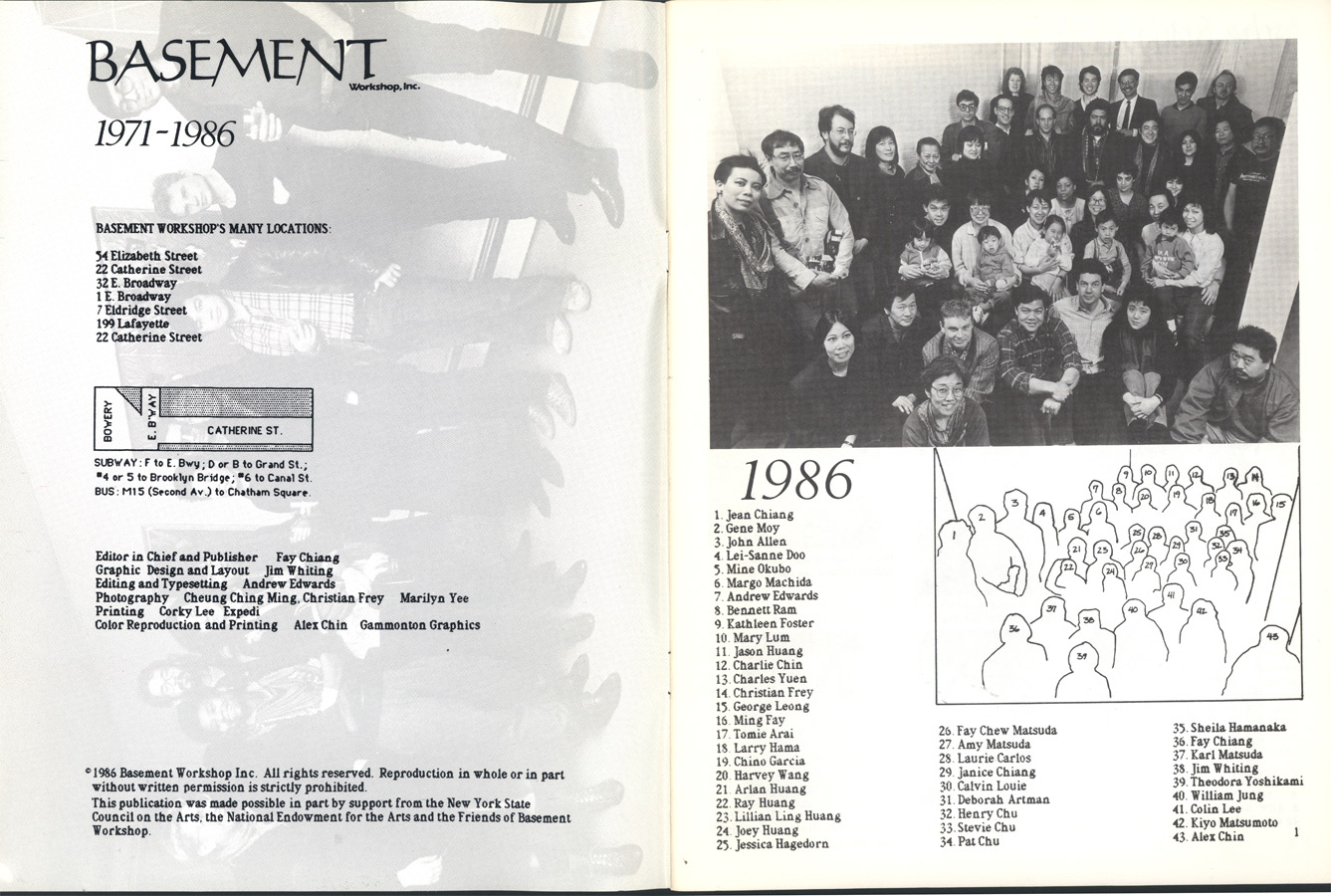

Inspired by the civil rights, Black Power, and liberation movements of the era, which sought to collectively overturn the racial and economic order that divided and impoverished people of color since the country’s beginning, a new generation of activists of Asian descent came together to build their own Asian American Movement in the 1960s and 70s. Eschewing a traditional path, they chose a life and work which sought to improve conditions for their communities. In New York, an arts and activist collective which stood at the forefront of this Asian American Movement was the Basement Workshop. Basement grew out of a student-led study in 1969 which mobilized students from local universities to collect data assessing the needs of the New York Chinatown community. As part of the study, bilingual students conducted door to door home visits with more than 500 families and urban planning students surveyed the neighborhood’s aged infrastructure. The experience drew together and introduced to each other like-minded young people of varied skills and backgrounds interested in getting involved in the community. To serve as a home base for this group, the student director of the study, Danny NT Yung, along with a few members, chipped in to rent a cheap basement in the tenement building of 54 Elizabeth Street and founded the Basement Workshop in 1970.

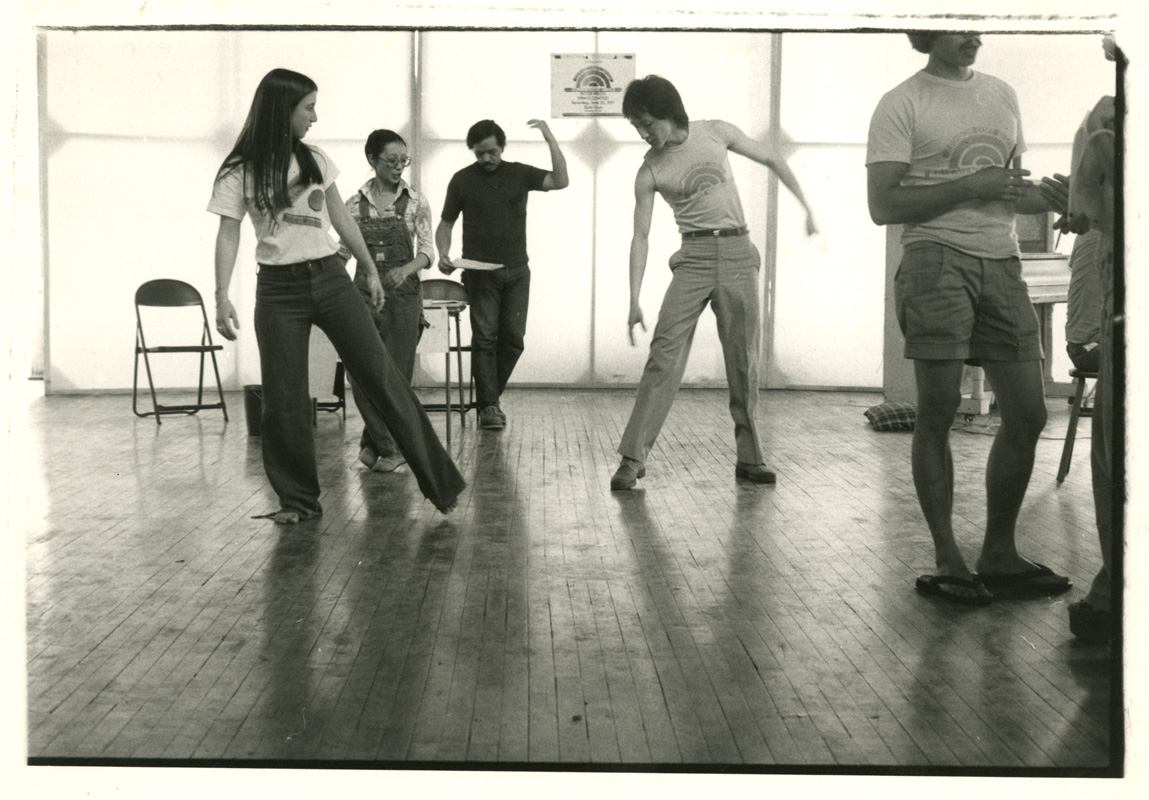

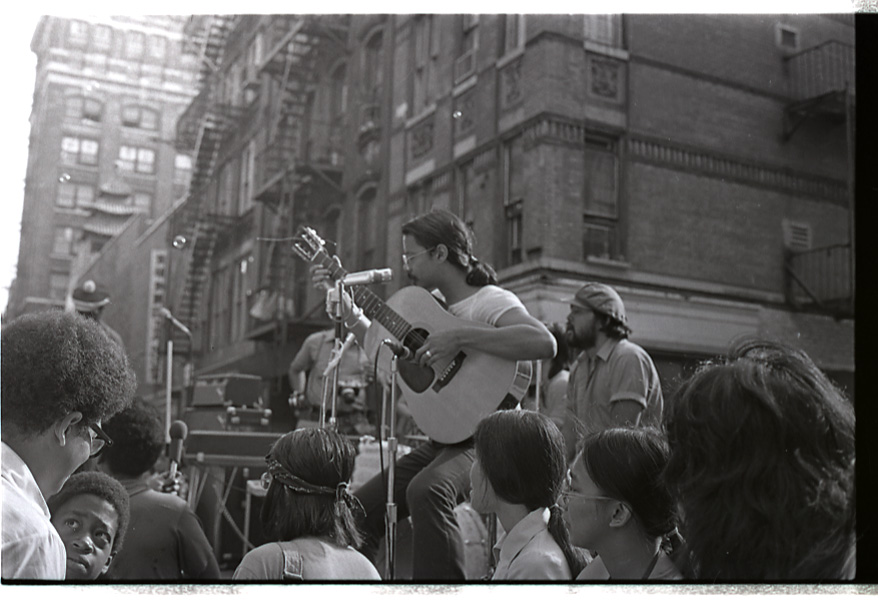

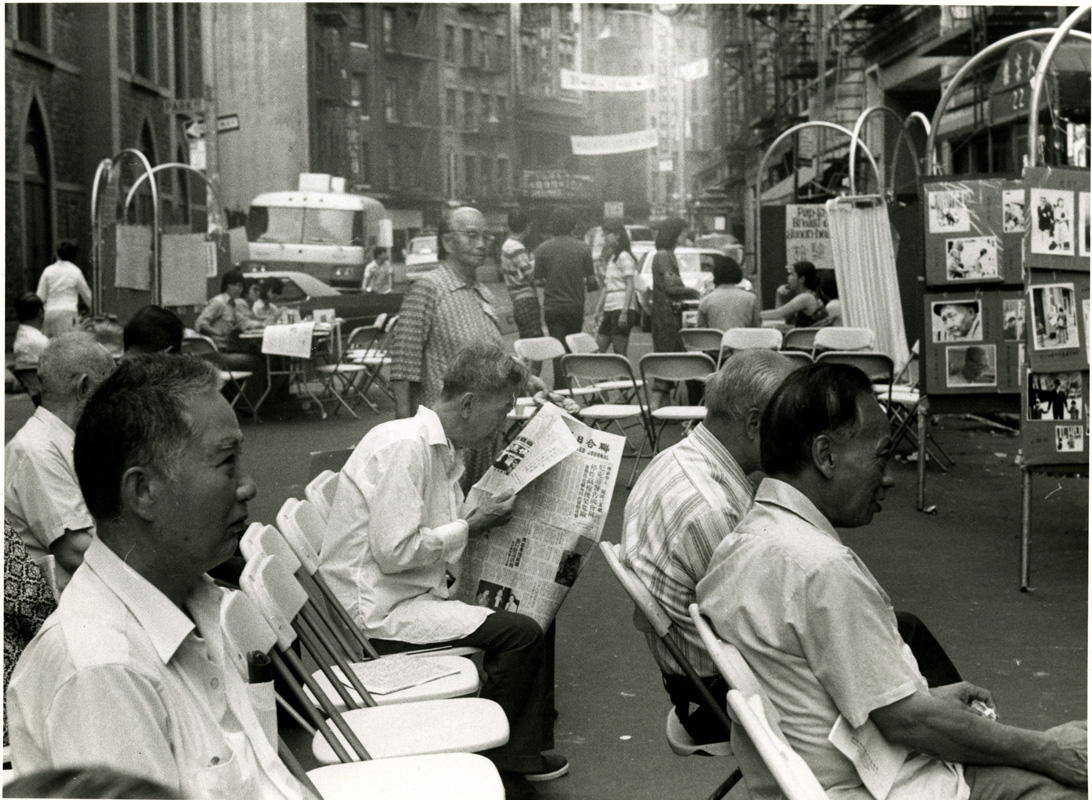

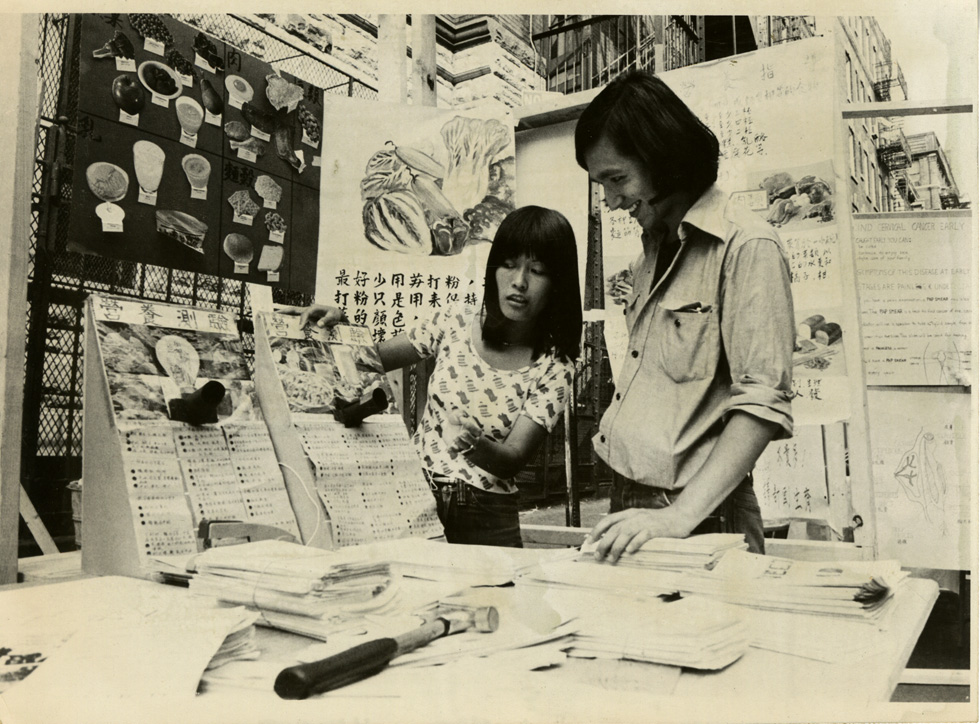

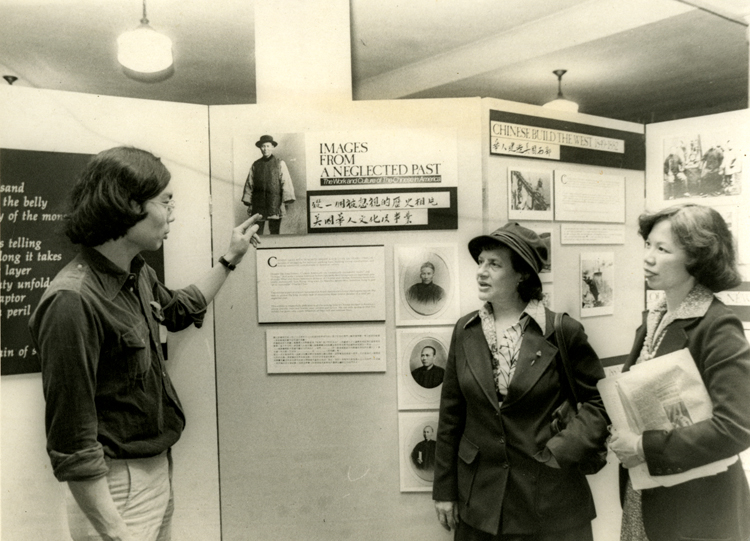

Far from comprehensive, the selected photographs document just a few of members’ wide-ranging programs and activities. Perhaps the most well-known was that it offered a space for artists to collaborate and create a new Asian American counterculture, which gave voice to the experiences and perspectives of this first generation to identify with the term “Asian American.” Out of its creative arts arm came the important anthology of distinctly Asian American music, art and poetry, Yellow Pearl. It also provided a space for members to volunteer-teach classes for the community in photography, filmmaking, dance, and kung fu. At a time of active youth gangs, their free after-school and summer arts programs, street festivals, and field day competitions provided safe spaces for neighborhood children to have fun and cultivate creativity. They also taught free English language and civics classes to help immigrant residents communicate and pass their citizenship tests. Noting that many in the community were without healthcare, they organized the first of what became an annual health fair providing free bilingual health information and screening tests. Members interested in documenting the history of Chinatown, heretofore ignored by existing institutions, conducted oral histories, salvaged old photographs and documents thrown out as stores closed or tenants moved, scoured libraries and archives to collect information saved about Asian American history, and put together exhibits that they hoped captured the experiences of Chinatown’s working people. Members also fought for ethnic and Asian American studies at universities, protested against the refusal to hire Asians in the construction of the Confucius Plaza apartments in Chinatown, and lent their voices, photography and art skills to many more of the era’s social justice protests. Out of Basement and from its members came the Charles B. Wang Community Health Clinic, Asian CineVision, the New York Chinatown History Project, and a constellation of other organizational offshoots still a part of Chinatown and our city’s cultural landscape today.