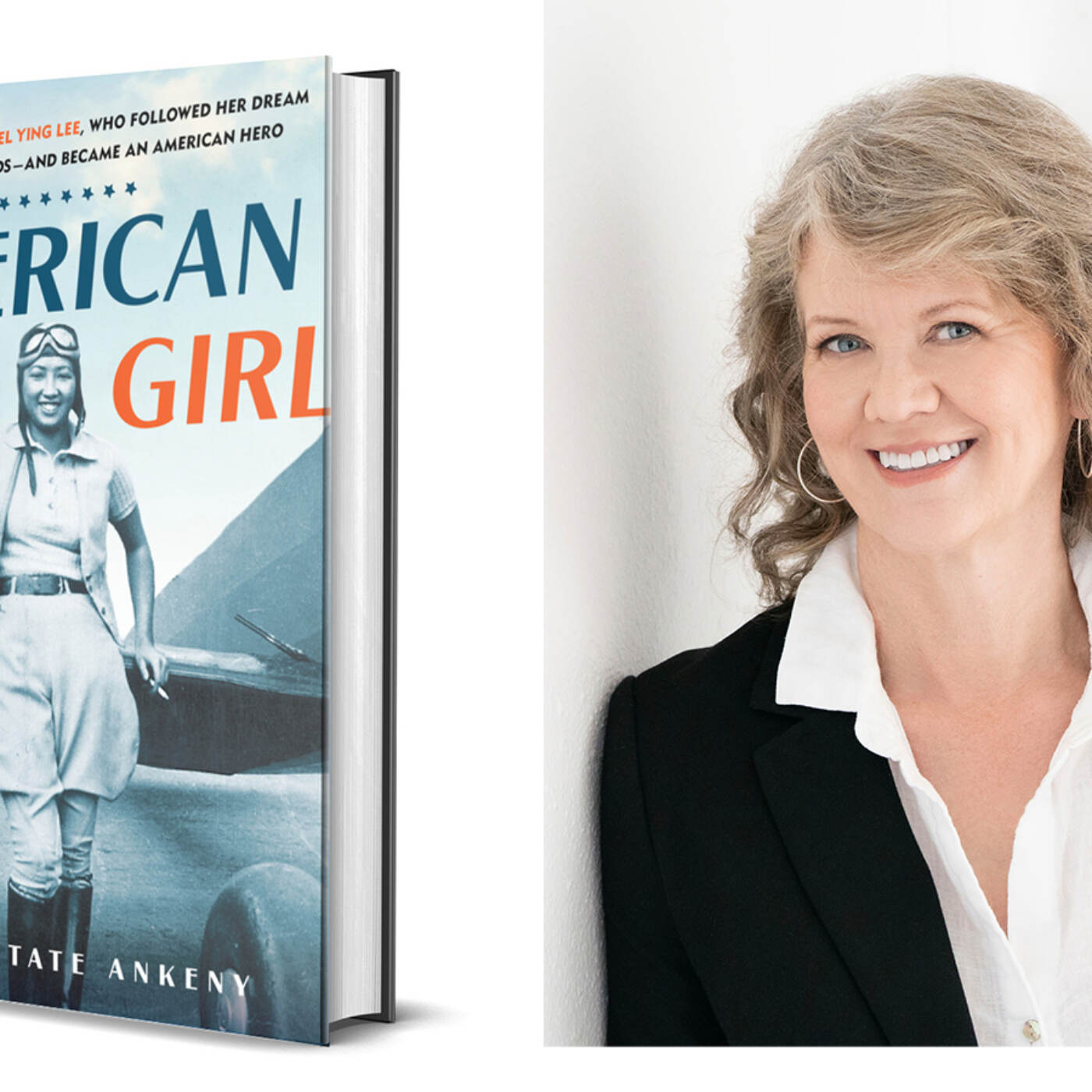

We wanted to share the stories of a few Chinese American heroes whose legacies remain even today, and invite you to celebrate them through a few related craft activities! Today, we’ll explore the story of a brave pilot, a world-renowned set designer, and an incredible Disney animator—all of whom are Chinese American!

First, let’s talk about Hazel Ying Lee (李月英), the first Chinese American woman ever to earn a pilot’s license and fly for the U.S. military. Hazel was born in 1912 in Portland, Oregon, to Chinese immigrant parents. She was the oldest of eight children.

Family Picture Taken 1927 in Portland, Oregon. Courtesy of Hazel Ying Lee & Frances M. Tong, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Collection.

She served as one of only two Chinese members of the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs), and worked to deliver military aircrafts and fighter planes during World War II. This was crucial to the war effort.

Hazel quickly emerged as a leader among the other pilots, and was described as “calm and fearless.” She was once forced to make an emergency landing at a wheat field in Kansas. A farmer, armed with a pitchfork, chased Hazel around her plane as he was shouting to his neighbors that the Japanese had invaded Kansas. Evading his attack, Lee told the farmer who she was and demanded he stop.

Hazel Ying Lee in Uniform. Courtesy of Hazel Ying Lee & Frances M. Tong, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Collection.

Unfortunately, Hazel died in the line of duty from injuries while delivering a fighter jet to Montana, where confusion in the control tower resulted in a collision between her and another plane. She was only 32, and was the last to die in service during the WASP program. She was laid to rest in a non-military funeral.

Despite their contributions to the war effort, WASPs only had civilian, not military status. This meant that they were not entitled to veteran benefits like disability compensation, medical benefits, education stipends, and government backing on loans. Eventually, all WASPs were recognized as having military status, but it took until March of 1977. That’s more than 33 years after Hazel died. In 2010, she posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal.

Hazel was a hero who was patriotic despite widespread anti-Asian sentiment at the time, and her courage and strength will always be remembered!

Learn to make miniature versions of the planes Hazel once flew here with our MOCACREATE at Home: Soar with Hazel!

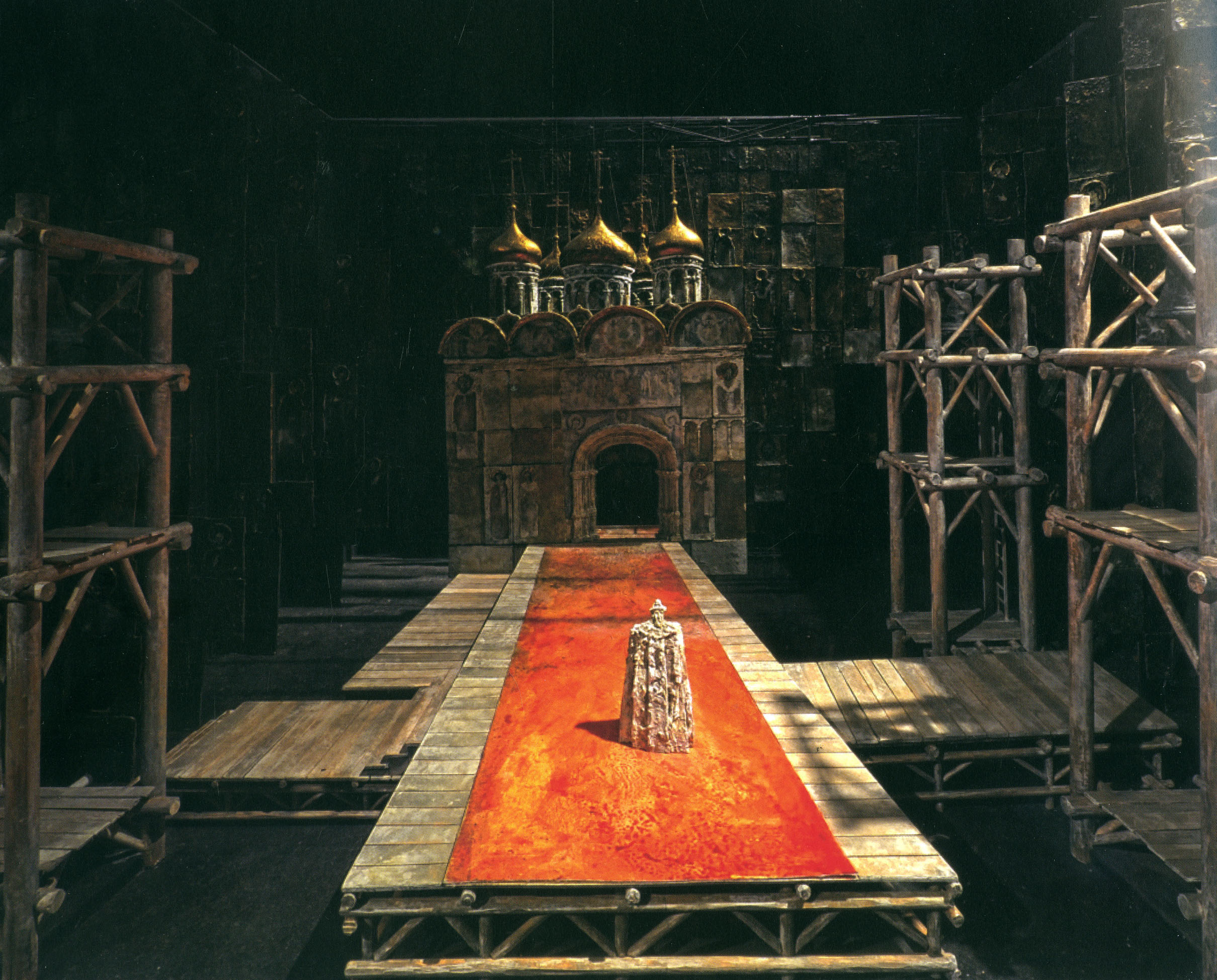

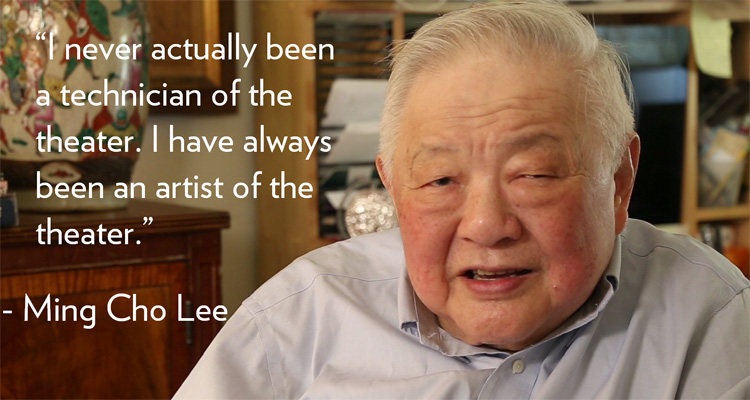

Next, let’s learn about Ming Cho Lee (李名覺), an incredible Chinese-American set designer and long-time professor at the Yale School of Drama. Lee was born in Shanghai, China, in 1930, and moved to the United States in 1949 to attend Occidental College. In 1954, he moved to New York and became an assistant for Jo Mielziner, a renowned Broadway set designer, marking the start of his lengthy and prolific career in stage design. Lee not only created sets for various theater shows such as Two Gentlemen of Verona and The Glass Menagerie, but also worked with world-renowned dance and opera companies such as Martha Graham and the Metropolitan Opera.

Scale model for “Boris Godunov (Coronation)” 1974, Metropolitan Opera, New York. Courtesy of Ming Cho Lee Family.

Over the course of his career, Lee designed over 300 productions, globally, for which he received numerous awards and honors, including a Tony Award for Best Scenic Design (1983), the Obie Award for Sustained Excellence (1995), a lifetime achievement Tony Award (2013), a National Medal of Arts (2002), and was inducted into the American Theatre Hall of Fame in 1998.

Sadly, Lee passed away last October, leaving behind a legacy of imagination and creativity that both redefined and completely transformed the field of set design.

Ming Cho Lee was interviewed by MOCA for the Journey Wall Oral History Project, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Institutional Archives.

Learn more about the process of set design and try building your own miniature set here with our Winter Wonderlands in Honor of Ming Cho Lee!

Lastly, let’s talk about Tyrus Wong (黄齐耀), a Chinese American artist whose work included painting, animation, calligraphy, murals, ceramics, lithographs, and kites. Although Tyrus had many talents, he is most well known for his work as the lead production illustrator on Disney’s Bambi (1942).

Tyrus was born in Taishan, China in 1910. When he was only nine years old, he and his father immigrated to the United States as “paper sons.” This meant they used false identities to immigrate because they were not allowed in by the Chinese Exclusion Act (read about the Act and its impact here). Tyrus and his father were both held at Angel Island Immigration Station and questioned, and although his father was quickly approved, ten-year-old Tyrus was detained as the only child on the island for nearly a month. He was lonely, afraid, and miserable, all at only 10 years old. This experience, combined with being separated from his mother and sister (who he never saw again after leaving China), is said to have impacted his work for and connection with Disney’s Bambi.

After passing successfully through Angel Island, Tyrus and his father lived in poverty in a run-down boarding house in Los Angeles. During this time, Tyrus’s father encouraged him to practice his calligraphy on newspapers with water in place of ink, marking his first ever foray into art. In junior high, Wong’s artistic talent was noticed by a teacher, who arranged a summer scholarship at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles. There, he found his true calling, and chose to continue studying as the Institute’s youngest student instead of returning to junior high. Over the next five years, Wong studied while also working as the school’s janitor, eventually graduating in the 1930s. Following his graduation, Wong worked as an artist for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), after which he founded the Oriental* Artists’ Group of Los Angeles, a groundbreaking organization that highlighted the work of Asian artists.

In 1938, Wong began to work at Disney as an animation artist during a time where Asian Americans were virtually nonexistent in Hollywood studios. This meant he had to face racial discrimination, slurs, and stereotypes at the hands of coworkers. At the time, Disney was having some trouble with deciding on an animation style for Bambi–as the follow-up film to Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Disney had intended to use a similar art style for the backgrounds of the film, but soon realized that the art style would not align with the narrative of Bambi.

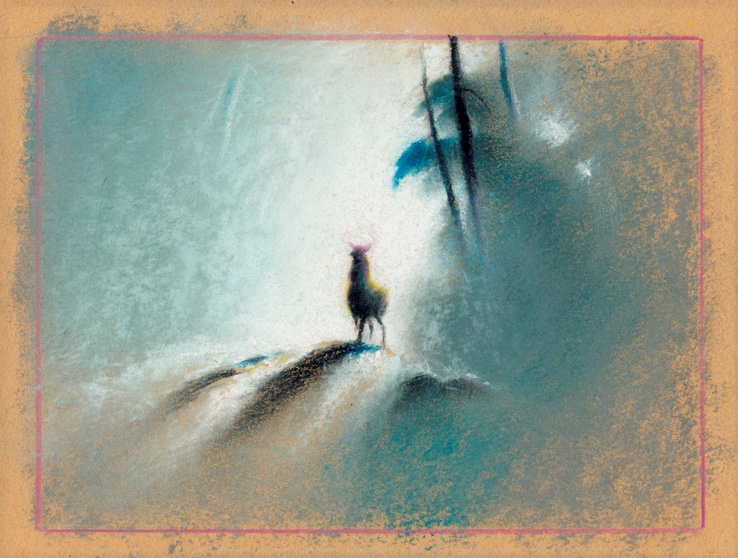

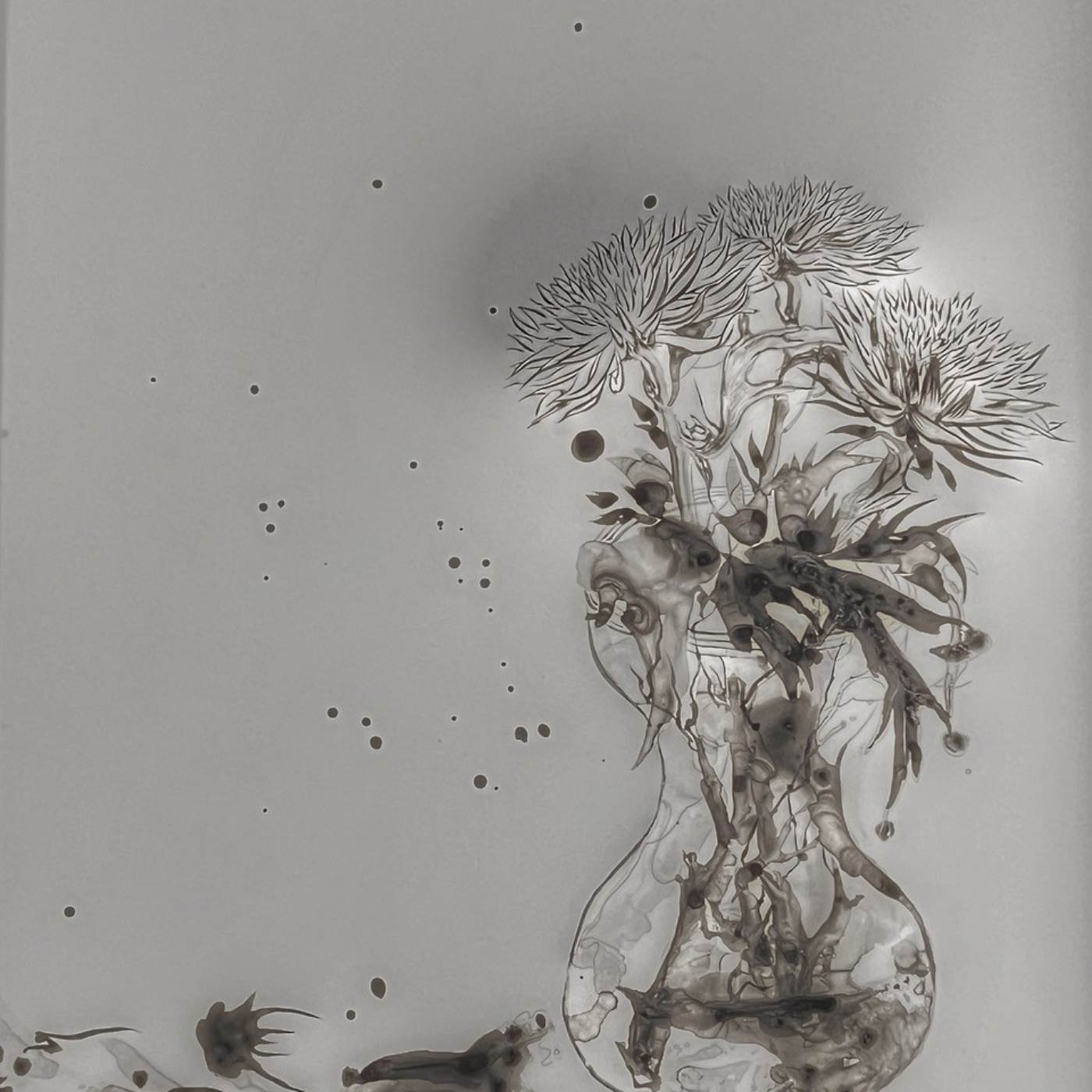

Wong saw an opportunity to use his unique background and abilities, making a few sketches of deer in a forest at home while the film was in pre-production. His art caught the attention of Walt Disney, who loved them, leading Wong to get his big break–he was unofficially declared an inspirational sketch artist for the film. Wong’s work was heavily inspired by traditional Chinese art from the Song Dynasty–rather than creating detailed portrayals of nature, he focused on the emotions evoked by his art. Over the course of two years, he used pastels and watercolors to create the illustrations that would influence and inspire every single aspect of Bambi, from the music to the special effects. Take a look at some of his sketches here, along with some comparisons to the actual film. Can you tell how his unique art style influenced the final film? How do the distinct qualities of his artwork (i.e. delicate brushstrokes) influence the mood of the scenes?

- Tyrus Wong (China, b. 1910) Bambi, 1942. Visual development, watercolor on paper. Courtesy of Ron and Diane Miller.

- Tyrus Wong (China, b. 1910) Bambi, 1942. Visual development, watercolor on paper. Courtesy of Mike Glad.

- Tyrus Wong (China, b. 1910) Bambi, 1942. Visual development, watercolor on paper. Courtesy of Tyrus Wong Family.

Despite his significant contributions to Disney, Wong was fired by the company in the aftermath of an employees’ strike (one he did not even participate in) in 1941. As a result, Wong never truly received credit for his work on the film, only appearing as a “background artist” in the credits. A year later, Wong began working for Warner Brothers, where he continued to work until he retired in 1968.

In retirement, Wong became a well-recognized kite maker, and focused on taking care of his wife, Ruth Kim, who was living with dementia. He only returned to art after her death in 1995. In 2001, Wong was finally formally recognized for his work by being named a Disney Legend. The Disney Family Museum created a retrospective exhibit to showcase his work in 2013, titled “Water to Paper, Paint to Sky.” In fact, the exhibition was actually shown at the Museum of Chinese in America in 2015! Take a look at the exhibition here.

Tyrus with closed centipede kite. Photograph and Copyright Sara Jane Boyers.

Wong passed away at the age of 106 in 2016, and was survived by his three daughters and two grandchildren. His work and influence continue to inspire leading animators today and, undoubtedly, will continue to inspire those of the future.

Learn more about Tyrus Wong’s story and try your hand at painting landscapes with our Landscapes a la Tyrus Wong with MOCACREATE!

* A term now known to be offensive meaning “of, from, or characteristic of Asia, especially East Asia.”

MOCACREATE is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council; by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature; and by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.